Where We've Been...

Compared to many dog breeds, the German Shepherd has been in existence for a relatively short period of time—just over 100 years. The breed is world renown for its intelligence, loyalty and versatility. From it’s inception, the dogs’ form and function have varied by region—yet breeders focused on maintaining the original qualities as set forth by the breed founder. Qualities such as strength, intelligence, soundness and working ability. As with many breeds, the dogs’ form and function have transformed over time. There are distinct differences between American-bred dogs and German dogs—between working-line dogs and show-line dogs. Some will argue that these transformations have lead to the detriment of the breed, overall, while others believe firmly that without change and adaptation, no breed can flourish.

At GSDLiving, we see the pros and cons to both arguments. We believe there is a place for impeccably skilled working dogs, breathtaking show dogs and invaluable service dogs and companions—the definition of versatility. The goal of any reputable German Shepherd breeder should be to strive to produce dogs capable of performing their desired function. However, that desire for perfect form and function should never come before sound health and temperament.

So walk with us as we take a brief journey through time with the breed. Included are a sampling of our foundation dogs as well as images and illustrations of some of our dogs, today. Some will find this journey fascinating—and be encouraged—while others might feel a sense of sadness at what has been lost in the breed. Either way, it is important to remember that there isn’t anything that can’t be improved upon with education, collaboration and commitment. So let’s take a look at where we’ve been and where we are now.

Max Emil Friedrich von Stephanitz, the breed founder, was born in Dresden, Germany, in 1864. He was known as having a intense interest in shepherding dogs. Throughout early adulthood, he would frequent regional dog shows—learning as much as he could about the breed. One of his early observations was an overall inconsistency in body type and temperament among the dogs throughout the region. So it was not long before he embarked on a life-long journey to create what he hoped would become the ultimate working dog.

Von Stephanitz was also a career cavalry officer and worked at the Veterinary College in Berlin. It was here that he studied canine biology, anatomy—and the physiology of movement—all of which he would use later to help define the traits he desired in his foundation dogs.

In the mid 1890s, von Stephanitz purchased property near Grafrath where he began his breeding program. His initial goal was to improve the local dogs of the region—but ultimately, the dream would be to create a better working dog that could be used throughout Germany.

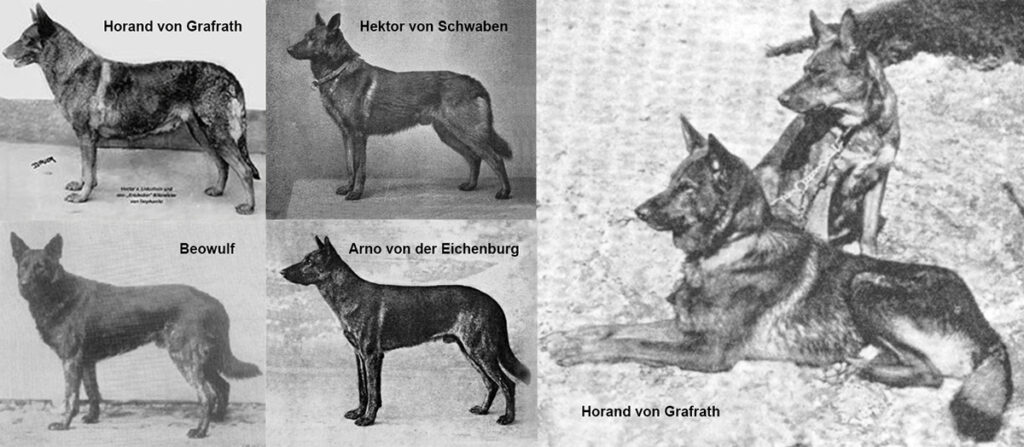

Von Stephanitz purchased his first stud dog, Hektor Linksrhein, in 1899 and changed the dog’s name to Horand von Grafrath. Horand was a working dog with natural abilities. He was extraordinarily intelligent and was adapt at his craft. His skills were not something that could be taught. He was the first registered German Shepherd Dog and was the foundation of the breed—as we know it today.

Horand’s son, Hektor v. Schwaben, and his grandsons, Heinz v. Starkenburg, Beowolf and Pilot were also instrumental in the formation of the breed. Pictured are some of these early dogs. Notice the smaller head size, length of leg and the level back of these early dogs.

By 1899, von Stephanitz’s breeding program was off and running and to solidify his groundwork, he established the Verein für Deutsche Schäferhunde, SV. (German Shepherd Dog Club). In 1922, the first breed survey book, the Körbuch was published. The purpose of the breed survey is to determine and document a dog’s suitability for breeding based on physical qualities and mental stability. The breed survey would be required along with the dog’s show record and rankings. The success of the SV would lead it to become the largest breed club in the world. But there was more to come as von Stephanitz’s passion expanded to promoting the breed as more than just a shepherding dog. In a relatively short period of time, he solidified the ideal dog’s form and type. Von Stephanitz’s motto, “utility and intelligence” would define the breed. To him, a dog’s worthiness was based on its intelligence, temperament and structural efficiency. Beauty was secondary.

The first German Shepherd Dog exhibited in the United States in 1907, just three years after its debut in the country. By 1913, the German Shepherd Dog Club of America (GSDCA) had formed and the club hosted its first specialty show just two years later. As the U.S. entered into World War I, anything associated with Germany became taboo in the U.S., so the American Kennel Club (AKC) decrees the elimination of the word “German” from the breed name and GSDCA became the Shepherd Dog Club of America. In England, the name of the breed was changed to the Alsatian. Decades later, in 1977, the word “German” was eventually added back into the breed name.

The end of World War I brought new appreciation for the breed as returning U.S. servicemen told heroic tales of courage and the striking intelligence in their war dogs. And movies like Rin-Tin-Tin and Strongheart boosted the popularity of the breed to unimaginable heights. Strongheart is reported to have earned an astounding $2.5 million. During this period of popularity for the breed, puppy mills flourished, flooding the U.S. market with lesser quality dogs.

Meanwhile, in Germany, things were not going so well either according to von Stephanitz. He was growing increasingly dissatisfied at the trend of breeding oversized, square dogs with inferior temperaments and missing teeth. In an effort to turn the tide, he selected Klodo von Boxberg as world sieger at the 1925 sieger show. Klodo was dramatically different in type from any dog before him. He was lower stationed and short coupled—with a far-reaching gait. Later that year, Klodo would be imported to the U.S. and became one of the foundation dogs of today’s North American lines.

Pfeffer von Bern entered the scene in the U.S. in 1936 and Odin vom Busecker-Schloss arrived two years later. Pfeffer took both German Sieger and American Grand Victor (GV) in 1937 and brought a more uniform type of dog to U.S. bloodlines. But his contributions to the breed were not without cost. Pfeffer carried the gene for long coats and produced progeny with missing teeth, faulty temperaments and cryptorchidism—all of which still plaque the breed today. These dogs did however still maintain near-level backs, strong pasterns and good length of body. More depth of chest began to appear as well as a larger, more powerful head.

Max Emil Fredrich Von Stephanitz died in 1936, at the age of 71, on the 37th anniversary of the formation of the SV. Today, the club is headquartered in Augsburg, Germany.

After the passing of von Stephanitz, the SV continued its quest to improved and control quality and consistency within the breed through the introduction of the a-stamp hip and elbow rating system, a tattoo identification system and stricter requirements for the award of top ratings. During this same period, the separation of U.S.- and German-bred dogs became more defined. An emphasis on show status became the norm in America and professional handlers took control of the sport. Acceptance of the early breeding of dogs—before their true genetic value was apparent—became common practice. A practice that is still in place today under the AKC.

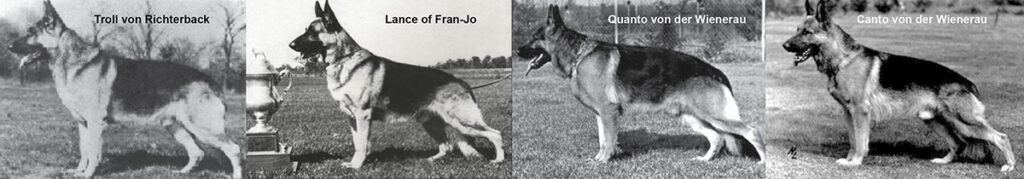

U.S. breeders infused outcross blood during the 1950s. A dog by the name of Troll von Richterback became Grand Victor in 1957. He brought in virtues such as increased rear drive, more bone and stronger head. But once again, the line also bought heartache with straight upper arms, weak ears and color and pigment faults.

One of the the biggest turning points for the American dogs came with the introduction of Lance of Fran-Jo, a dog who took the American and Canadian Grand Victor in 1967. Lance was the beginning of a new era in American-bred shepherds. The rising costs and lower quality of many of the dogs coming out of Germany led U.S. breeders to further take command of the breed. Lance infused U.S. lines with increased rear angulation, a straight, sloping top line and what would become an infamous side gait.

Two top stud dogs in Germany during the mid to late 60s were Quanto von der Wienerau and Canto von der Wienerau. Quanto’s influences included progeny that were medium sized, lower stationed, powerful dogs with good depth of chest and strong bone and expression. His faults included progeny with faded pigment, east/west fronts, cow hocks and short, flat croups.

During the mid 60s, stud dogs like Quanto and Canto von der Wienerau, and others, brought in greater angulation and a short, flat croup to progeny emerging from Germany.

One of the areas of concern with the breed in Germany during the 1960s was a decline in working ability. Hence, the SV instituted measures that placed greater emphasis on working titles. A schutzhund 1 title and a passing endurance test (AD) were required for completion of the breed survey and thus eligibility for breeding. Temperament and courage tests became more demanding and the club forced breeders to improve the health and structure of their breeding stock. Since club officials were also judges at the sieger events, it was prudent for breeders to present only those animals meeting or exceeding the requirements demanded by the SV. Additionally, a schutzhund 3 become mandatory for any dog seeking the coveted VA award.

Now that we have a basic understanding the how the breed’s foundation dogs looked and functioned, let’s take a look at where the breed stands today and how form and function has or has not changed. Over the decades, the breed has evolved into two distinct categories—working-line dogs and show-line dogs. Working-line dogs include West German, East German/DDR and Czech dogs. Show-line dogs include West German and American/Canadian dogs. Let’s take a closer look at these two distinct types of dogs and how and why they have evolved into what we see today.

Where We Are Now

Despite the separation between show lines and working lines, the legacy of von Stephanitz’s breed stands and the German Shepherd Dog remains one of the most popular breeds—world wide. In 2019, the German Shepherd was the #2 most popular breed in the U.S. Sharing our lives with these amazing dogs is still a luxury and something we continue to embrace.

Today’s working-line dogs remain fairly consistent in form and function to von Stephanitz’s original vision for the breed. These dogs are powerful, medium in size—with intelligence and sound working abilities. There are some lines that are producing dogs above the established height and weight for an optimum working dog, so keep this in mind when sourcing any new dog. Drive can also vary among lines and those seeking world-class working ability will need to seek lines proven to produce dogs with these innate characteristics. Depending on the primary function of a line, degrees of bone and body mass also vary as seen in the larger, more muscular build of DDR dogs.

What we want to focus on in this section, in particular, is the change in form and function of show-line dogs. The primary function of the German Shepherd show dog has shifted from that of being an agile, clear minded working dog—as initially envisioned by von Stephanitz—to that of a flashy, powerful mover. After all, there is no other breed of dog that can out trot a well-bred, show-line German Shepherd Dog.

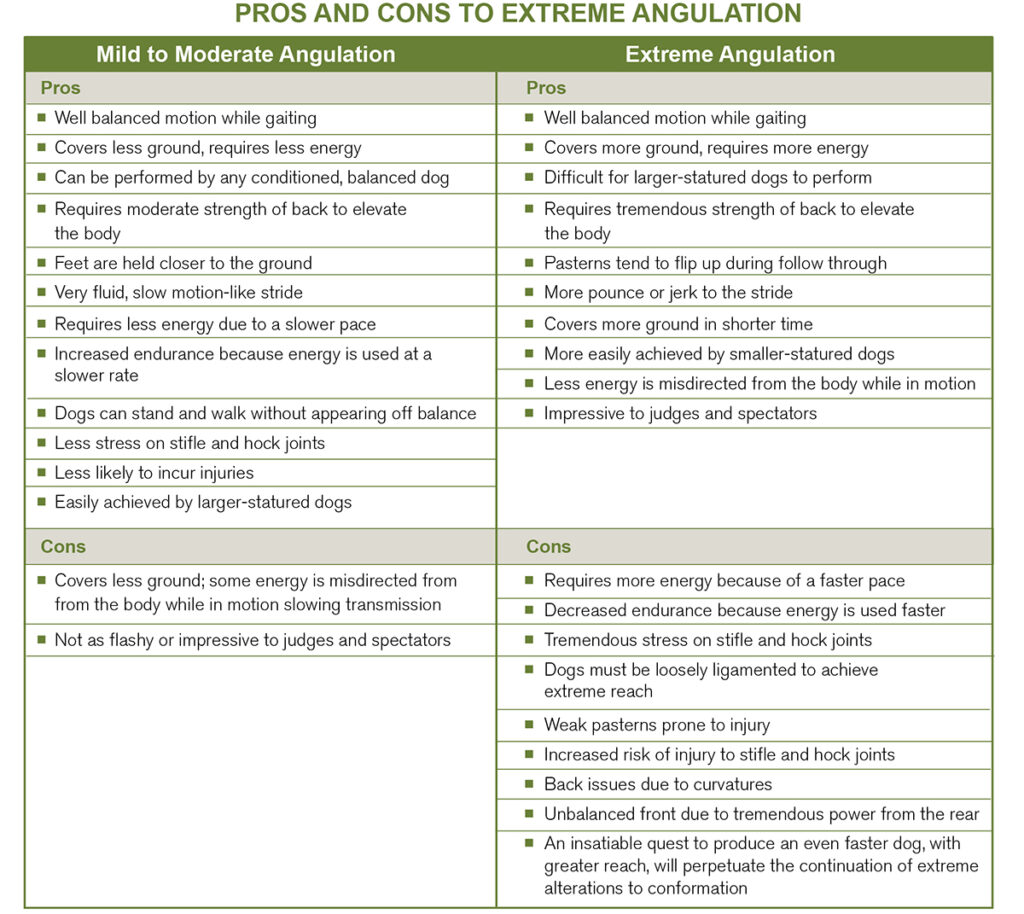

In order to get the power to move around the ring to the degree demanded by show-line breeders today, modifications were needed to the overall structure and physiology of the German Shepherd show dog. Whether you support these changes or not is not our focus, but rather, we want to illustrate more clearly what changes have been made and why. It’s also important to understand how these changes have affected the show dog’s overall performance and function.

The primary function of today's German Shepherd show dog has shifted from that of an agile, clear minded working dog—to that of a flashy, powerful mover.

What Is Angulation?

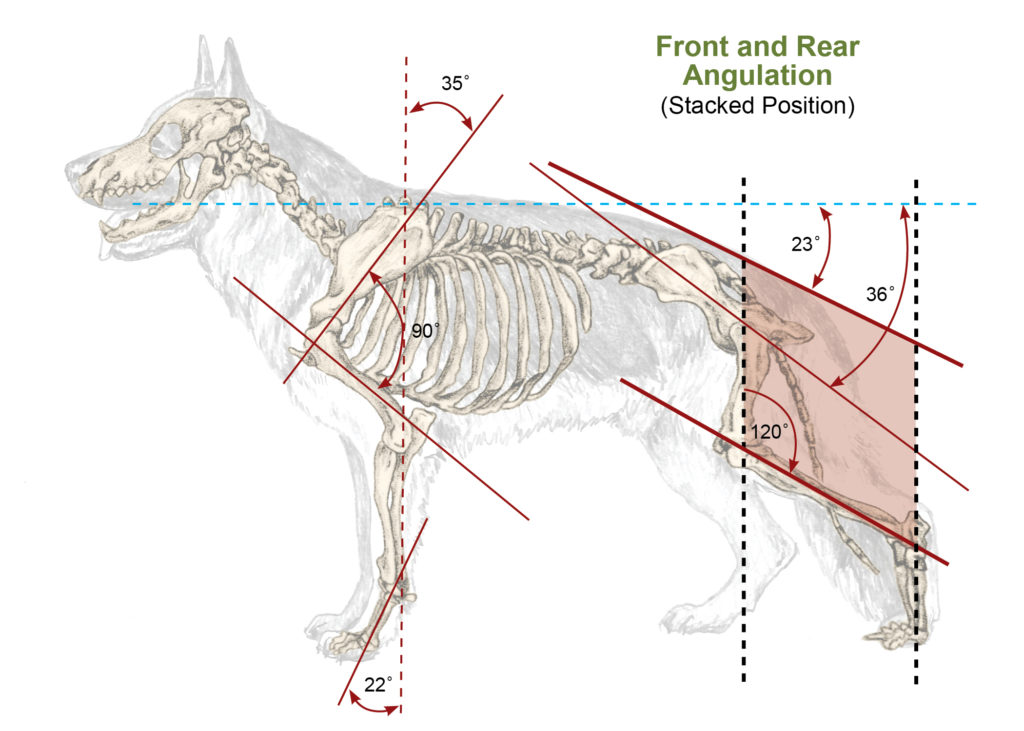

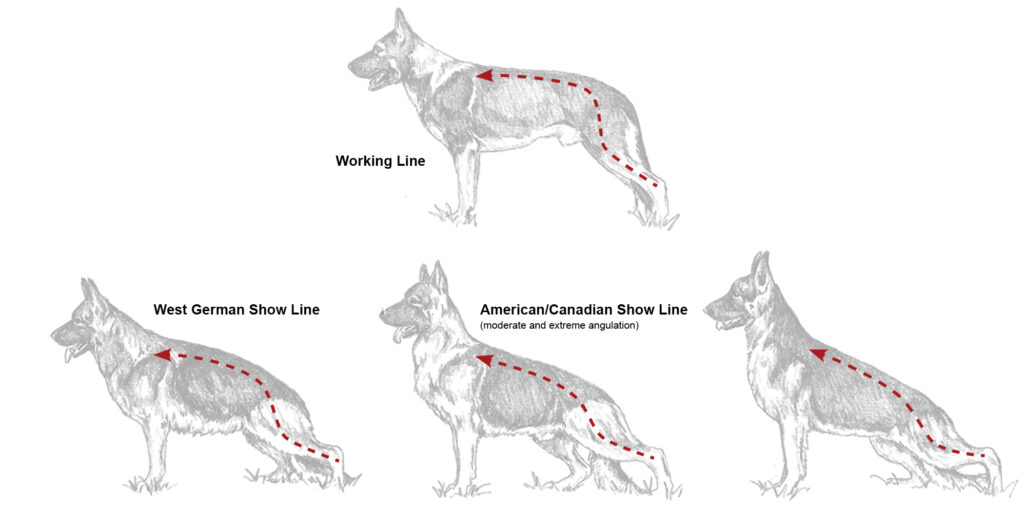

Angulation refers to the angle (degree of slant) between two or more bones surrounding a joint. In show-line German Shepherds, it is rear angulation that distinguishes it most from working-line dogs.

Anatomically, front angulation is usually dictated by the length of the upper arm (humerus). A short upper arm results in decreased front angulation and restricted movement. The scapula and humerus should be approximately equal in length. Rear angulation is determined by the length of the lower leg bones (tibia/fibula). The longer the lower leg, the greater the rear angulation and rear reach. The femur and the tibia/fibula should also be approximately the same length.

NOTE: A German Shepherd must be stacked correctly to accurately determine angulation. This means the hock on the extended rear leg must be positioned perpendicular to the ground and the forelegs must be positioned directly under the body in a straight line down from the withers. An over stacked dog (where the rear leg is pulled a great distance away from the dog) can appear overly sloped and off balance whereas an under stacked dog can appear horse-backed. This is why professional handlers are important. A great handler can make a average dog look exceptional and an inexperienced handler can make an exceptional dog appear inferior. When studying the conformation of a dog from photographs or viewing online, be aware that positioning can completely dictate how the handler wishes to portray the dog (actual or disguised). Always be cognizant also of photo manipulation as all professional, stacked shots have been altered to enhance the overall appearance of the dog. Seek third party references to confirm actual structure and conformation.

Angulation is discussed in greater detail on the Illustrated German Shepherd page on this site.

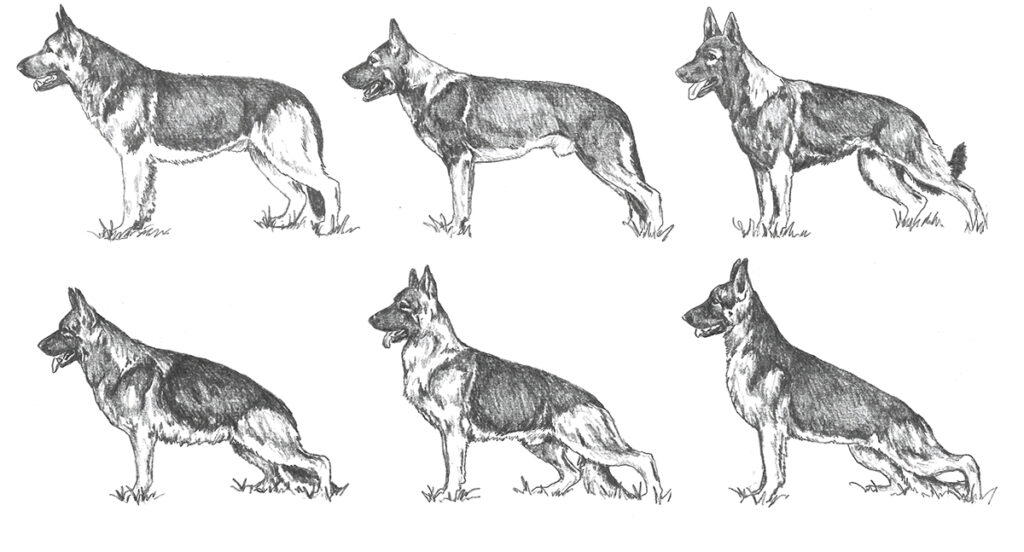

Below are a few examples of the differences in angulation in current-day German Shepherd Dogs. As you can see, there are still lines of dogs with little to no rear angulation (in both show-line and working-line) and lines of dogs with moderate to extreme rear angulation. The degree of angulation is determine by the intended function of the dog.

Understanding Transmission

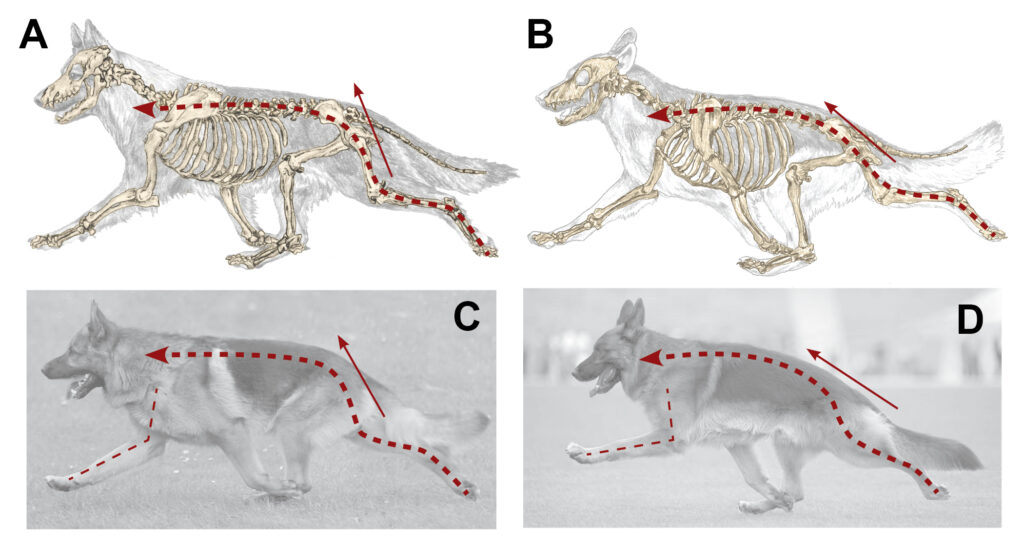

Transmission is the transfer (or forward movement) of energy through a German Shepherd’s body. In this section, we will show you where transmission begins and how it sets your GSD in motion. Great transmission begins with great conformation. If your dog lacks strength and firmness of back, or has a weak front or rear assemblies—its transmission (or forward propulsion)—will be compromised. Dogs that are loosely ligamented or poorly conditioned will also have faulty transmission.

Transmission begins in your GSD’s hindquarters. As your dog pushes off with its rear leg, energy travels from the hock, into the stifle and thighs, into the croup and back—and ultimately into the shoulders and forelimbs. As you can imagine, if your German Shepherd has poor hocks, there is little chance for good transmission. Energy will be directed toward the midline of the body (if cow hocked) instead of up and into the thighs. The incidence of injury in cow hocked dogs is very high due to tremendous stress placed on the hock and stifle joints.

If your German Shepherd has a powerful rear assembly with great rear reach—but it is not equally balanced in front—its rear components will overpower its front. This will cause a disruption in transmission and ultimately a restricted rear reach. The hind feet will likely strike the forefeet, causing your GSD to move crabwise—or even result in a high, over exaggerated front reach. Transversely, if the reach of your dog’s hindquarters is weaker than its forequarters, front reach will decrease to compensate for the its poor rear action. Every component of the body must be balanced to achieve fluid, effortless motion with the least misdirection (or loss) of energy.

The pelvis receives all the energy generated by the rear and serves as a bridge to allow that energy to pass seamlessly into the back. The amount of energy taken in by the pelvis is tremendous. Unlike the scapula, the pelvis is not connected to the spine with muscle, but is fused to the sacrum. A German Shepherd puppy that is born with a steep pelvis will have a steep pelvis as an adult. The angle does not change with maturity. If your GSD’s pelvis is too steep or too flat, it will direct energy up and away from its body and slow the transmission of energy from the hindquarters.

The back is another critical component involved in transmission. Once energy passes through the pelvis, it moves into the spine toward the forehand. A strong, firm back is essential. Any weaknesses will cause the dog’s torso to bounce or sway as it moves. This up and down, or side-to-side motion, causes energy to be misdirected and move in directions other than straight forward. While in motion, the back should remain straight and firm.

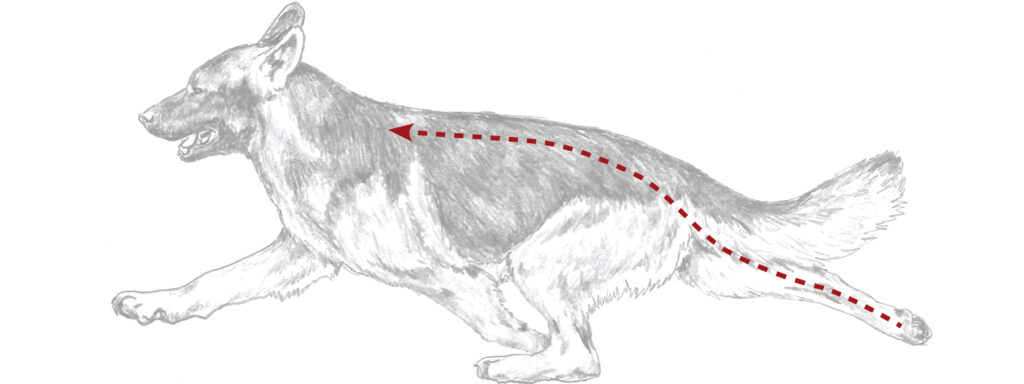

To produce a dog with an extreme, far-reaching gait, breeders select animals capable of transferring energy directrly from their hocks to their front assemblies with minimal loss of forward propulsion.

To explain better how to achieve a straight, powerful transfer of energy through a dog, see the illustrations below. The two dogs at the top of the first diagram (A and B) depict well-balanced dogs in motion. The front and rear reach on each is equal. The primary difference between dog A and dog B is in the flow of energy (transmission) through their bodies. Dog A is less angulated—meaning it has a more level back and decreased pelvic slope. Though this dog can move smoothly and with ease, the sharp turn at the juncture of the thigh bone and pelvis and at the pelvis and back will redirect energy up and out of the body instead of toward the front of the dog. This also increases the amount of stress on these two critical junctures. Dog B on the other hand, has more curve to its back and increased pelvic slope—so the flow of energy moves in a more direct path from the hock to its front assembly. Less energy is being directed up and out of the body. Dog C, another less angulated dog, also has energy being directed up and away from the body, while dog D does not.

Note however, another important difference between dog C and dog D. The amount of energy being generated from the rear of dog D is so great that it is overpowering its front—causing the dog to flip up its front legs in an attempt to increase front reach. The dog also has a short upper arm contributing to its weaker front. This imbalance of energy will cause this dog to tire much faster then the other dogs in this example—reducing its endurance.

West German show line vs. American/Canadian show line

Breeders have discovered that there are two ways to alter the conformation of a dog with the intent of increasing reach. The first, as discussed above, is the direction West German show-line breeders chose to undertake. Their dogs have a curved back; short, steep croup; and increased rear, lower-leg length. The American/Canadian breeders chose a slightly different approach. Their dogs have straight, sloping backs; long flat croups; and very long rear, lower-leg bones. The added length to the rear lower leg (that is now nearly parallel to the ground) pulls the rear closer to the ground and pushes the hock back and further away the body. The result is a straighten path for the transmission of energy.

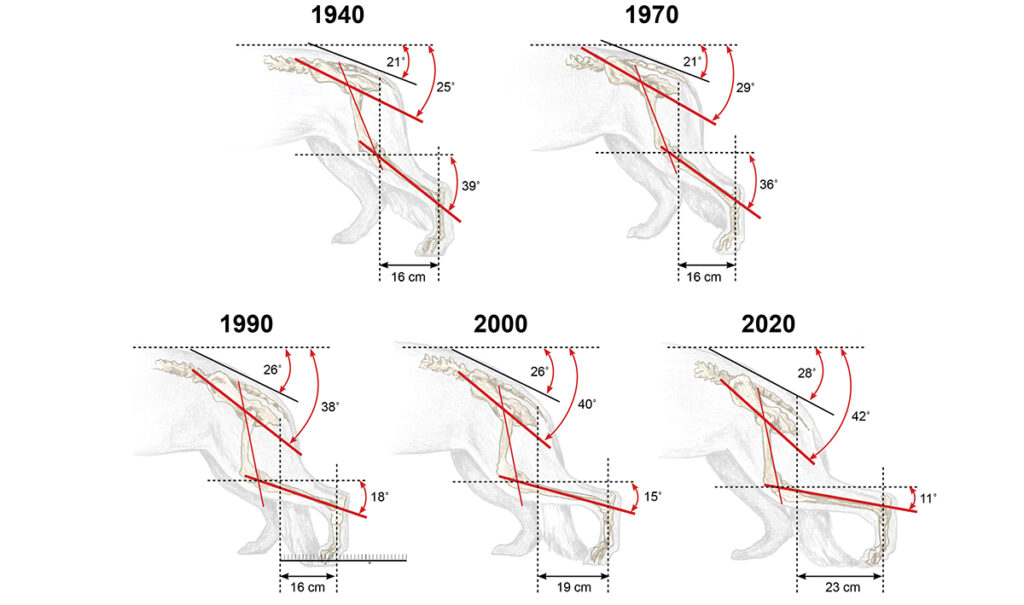

The final illustration below summarizes the evolution of rear conformation in the show-line German Shepherd Dog from the 1940s to today. With the dog correctly stacked (hock perpendicular to the ground), the anatomical changes that have evolved include:

- Increased slope of croup from 21˚ to 28˚

- Increased pelvic slope from 25˚ to 42˚

- Increased length of rear, lower-leg bones, distance between the tip of the pelvis (ischium) and the hock, from 6.3″ (16 cm) to 9″ (23 cm)

- Decreased slope of rear, lower-leg bones from 39˚ to 11˚, making them nearly parallel with the ground

Source: The Curved Back in the German Shepherd Show Dog, Louis Donald.

GREATER REACH AND IMPROVED TRANSMISSION IS WHY THE CONFORMATION OF THE SHOW-LINE GERMAN SHEPHERD HAS BEEN CHANGED OVER THE YEARS. The saying, “the fastest way to get from point A to point B is a straight line,” holds true when explaining transmission. If you want your line of German Shepherds to have fast, flashy, exaggerated gaits, you breed dogs that can transfer energy from the hock to the front assembly quickly and in as straight a line as possible. To do this, you can breed dogs with: 1) a curve to their back and loin; a short, steep croup and extra long rear, lower-leg bones OR 2) a straight back; long, flat croup and extremely long rear, lower-leg bones that are near parallel with the ground.

Final Thoughts

At GSDLiving, we have spent years studying German Shepherd anatomy and physiology in an effort to better understand how our dogs’ bodies work and what sets them into motion. Through our research, we now understand what changes were necessary to achieve that extraordinary, extreme gait that is so coveted in the show ring—world wide. But one burning question remains. Why do our dogs need an extreme, exaggerated reach? Why are we altering their anatomy and physiology to perfect a skill that has little or no use outside of the show ring. And is the potential damage done to their bodies worth that trophy or title that is bestowed upon them?

And lastly, at what point will our dogs be gaiting at a level that is good enough? And will they be able stand and walk comfortably—and with ease—years after their show careers have ended?

We hope that this page will spar others to ask similar questions.