The Illustrated German Shepherd was created to help enthusiasts develop an eye for identifying world-class German Shepherds. By studying the breed standard, we gain a basic understanding of German Shepherd structure and temperament. However, since there can be no perfect dog, this guide offers the next best thing—visual references to illustrate what it takes to produce an outstanding representative of the breed.

The guide also serves as an excellent resource for those wanting to show and breed German Shepherds and can provide puppy buyers with the knowledge and confidence they need to quiz prospective breeders and identify quality puppies.

We present the German Shepherd Dog as a complete package—a dog capable of excelling in conformation, in the field and in our homes. The goal of a world-class breeder is to create and uphold a body type that is consistent and produce healthy animals—with stable temperaments—capable of performing a variety of functions. Learn to identify the faults and virtues in your breeding stock. By doing so, you can help to ensure a healthier future for all German Shepherds through education, collaboration and commitment.

NOTE: There are a number of variations to the breed standard and while this guide is not affiliated with any specific club or organization, it is a culmination of basic breed standard information—presented in a easy-to-follow, visual format. When showing any German Shepherd, please study and understand fully the standard recognized by your show organization.

General Appearance

The first impression of a quality German Shepherd should be that of a strong, agile, well-conditioned animal. It should appear balanced, with harmonious development from front to rear. The dog is longer than it is tall, deep-bodied, and presents an outline of smooth curves. It should appear regal and impressive, giving this impression both at rest and in motion. The ideal dog is stamped with a look of quality and nobility.

Height, Weight, Proportion

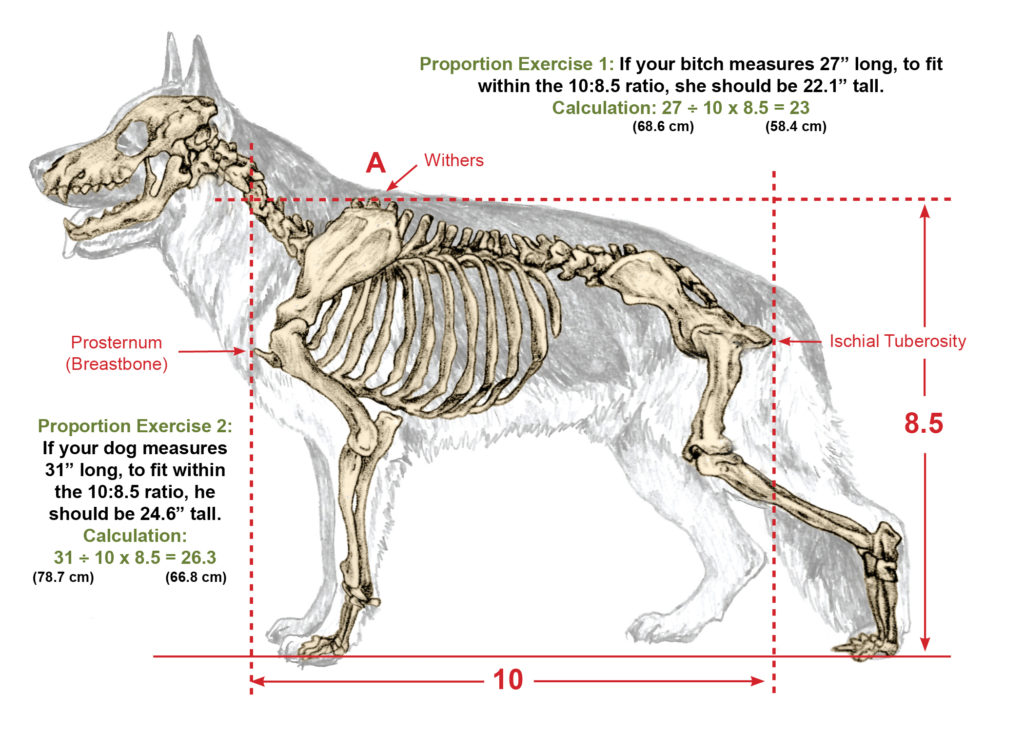

The first step to identifying a quality German Shepherd is to understand fully the basic anatomical structures of the dog. Correct conformation is paramount to the general appearance and overall performance of the dog. Learn to identify structural defects that can affect your dog’s form and function.

HEIGHT: Accurately measuring the height of your German Shepherd requires the use of a wicket. During conformation events, the wicket is first set to the maximum height as outlined in the breed standard. It is then placed at the highest point of the withers (A). If the base of the wicket touches the ground, your German Shepherd’s height falls within standard. If the wicket does not touch the ground, your dog is oversize. The desired height for males is 24 to 26 inches (60 to 66 cm); and for females, 22 to 24 inches (55 to 60 cm).

WEIGHT: At maturity, males typically weigh between 65-90 lbs. (30-41 kg), females 50-70 lbs (22-32 kg).

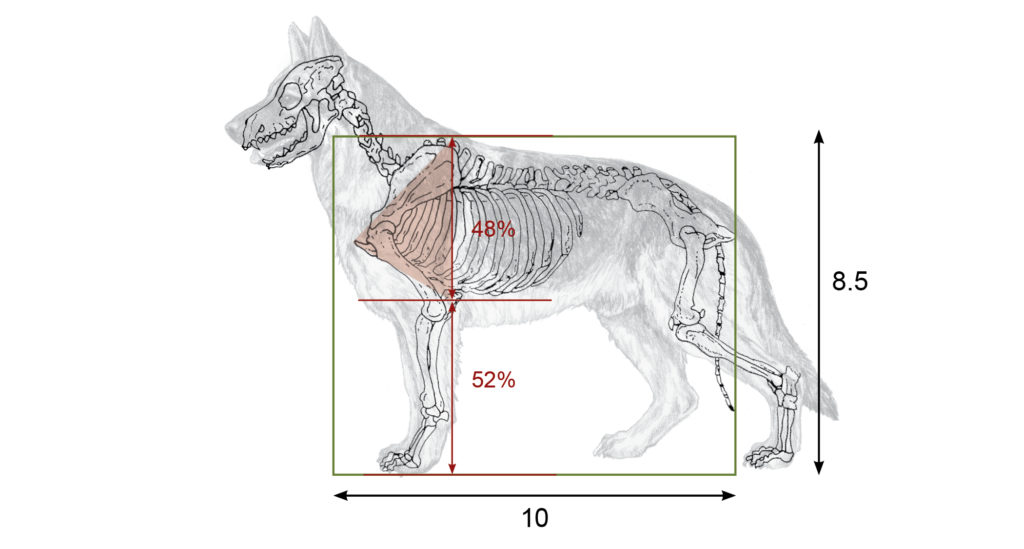

PROPORTION: The German Shepherd Dog is longer than tall, with the most desirable proportion as 10 to 8.5. The length is measured from the point of the prosternum or breastbone to the rear edge of the pelvis, the ischial tuberosity. The desirable long proportion is not derived from a long back, but from overall length with relation to height, which is achieved by length of forequarter and length of withers and hindquarter, viewed from the side.

Understanding Angulation

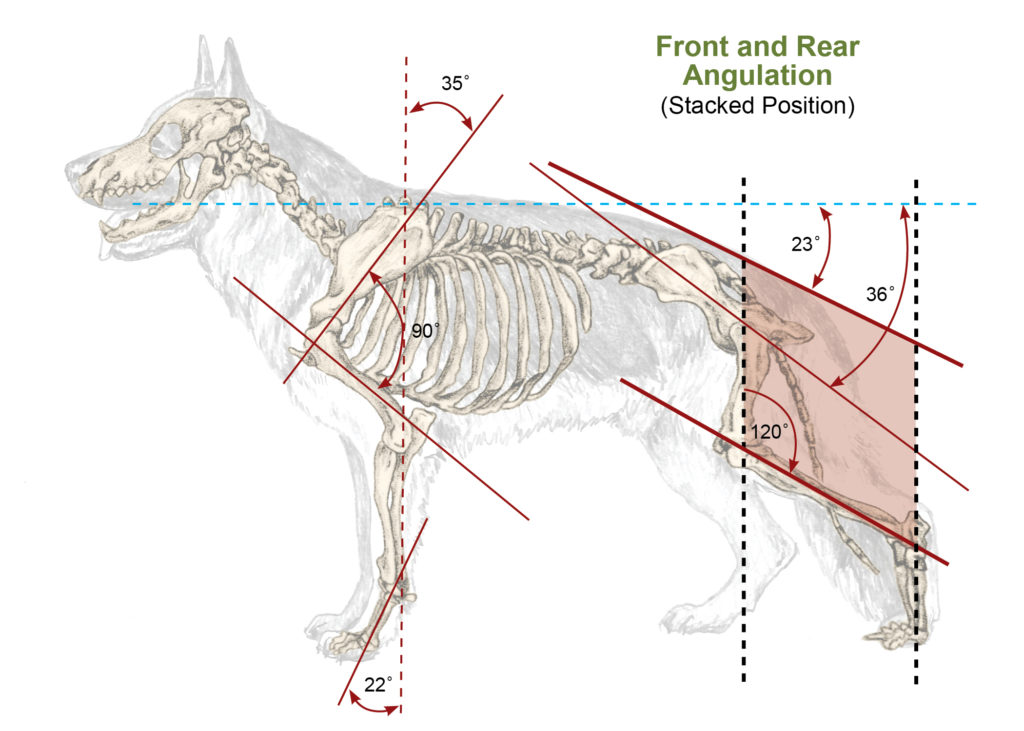

Angulation refers to the angle (degree of slant) between two or more bones surrounding a joint. The illustration below shows ideal front and rear angulation for German Shepherds.

Note: Your German Shepherd must be stacked correctly to accurately determine angulation. This means the hock on the extended rear leg must be positioned perpendicular to the ground and the forelegs must be positioned directly under the body in a straight line down from the withers.

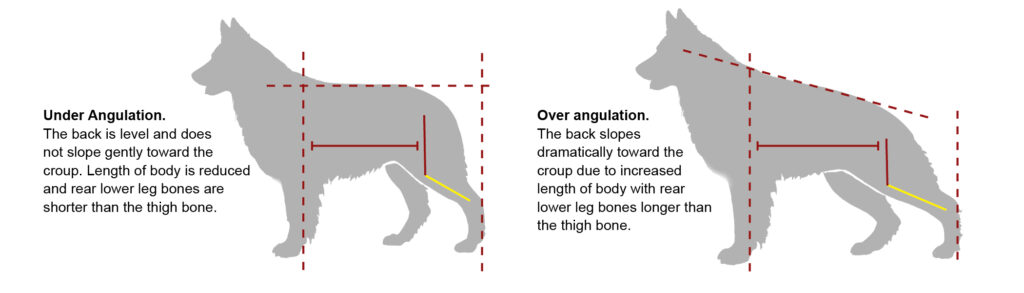

REAR ANGULATION

Rear angulation is determined by length of body (coupling), pelvic tilt and length of lower thigh bones.

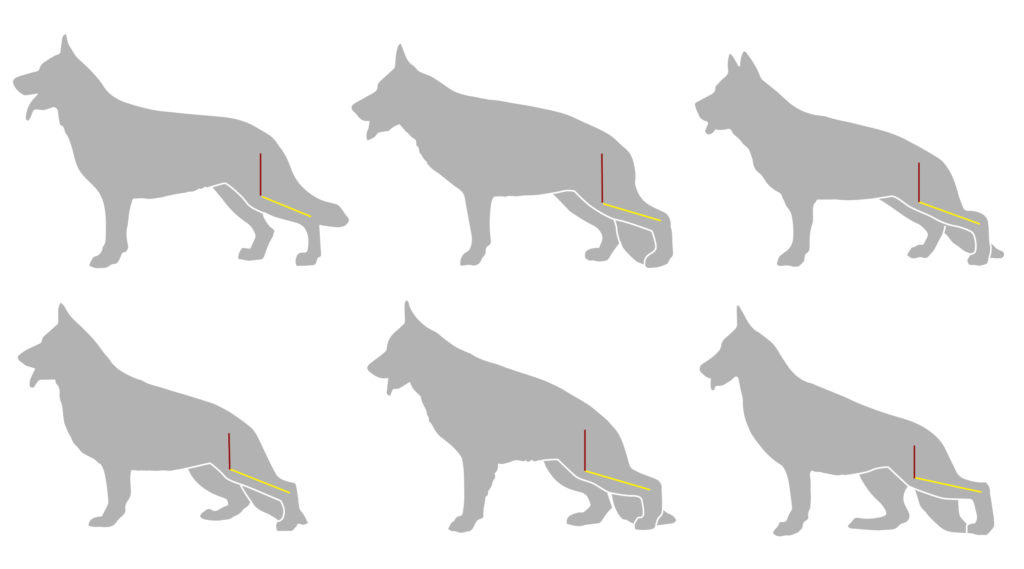

Examples of present day body types seen in German Shepherd Dogs.

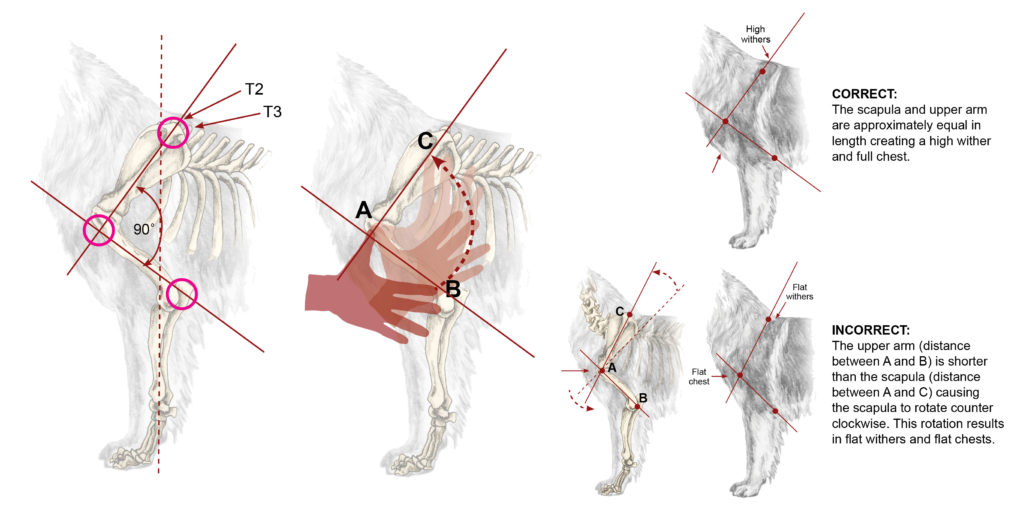

FRONT ANGULATION

Ideal front (shoulder) angulation for German Shepherds is approximately 35˚. When assessing your dog’s shoulder angulation, start by physically locating the shoulder joint—where the upper arm and scapula meet (A). Place your thumb on the joint and follow the humerus bone down to the elbow joint (B) and note the angle of your hand. While keeping your thumb stationery, swing your hand up until you feel the protruding rib of the scapula bone. This should be in line with your dog’s withers. Conformation judges frequently use this method to evaluate shoulder angles.

Anatomically, the highest point of the scapula should be positioned between thoracic vertebrae T2 and T3. The scapula and humerus should be approximately equal in length and be set at an angle of 90˚ from one another. An over angulated or steep shoulder will have a scapula that is angled at less than 35˚. Most steep shoulders are a result of a short upper arm and frequently cause a depression along the topline (flat withers) where the tip of the scapula (withers) would be positioned on a properly angulated dog.

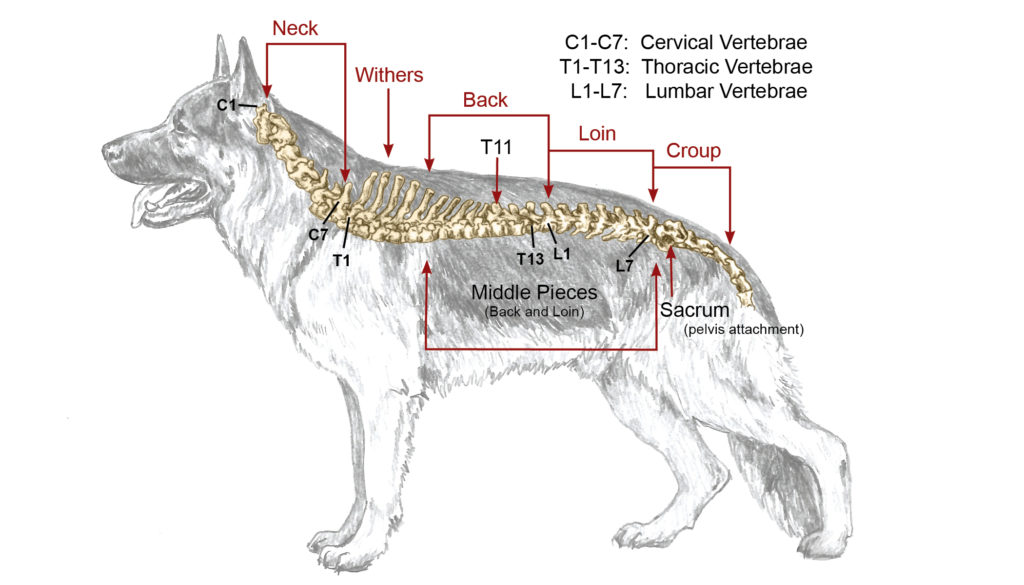

Spine, Middlepieces, Topline

Spine: The spine of German Shepherds consists of cervical, thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, the sacrum (where the pelvis attaches to the spinal column), and the coccygeal vertebrae of the tail.

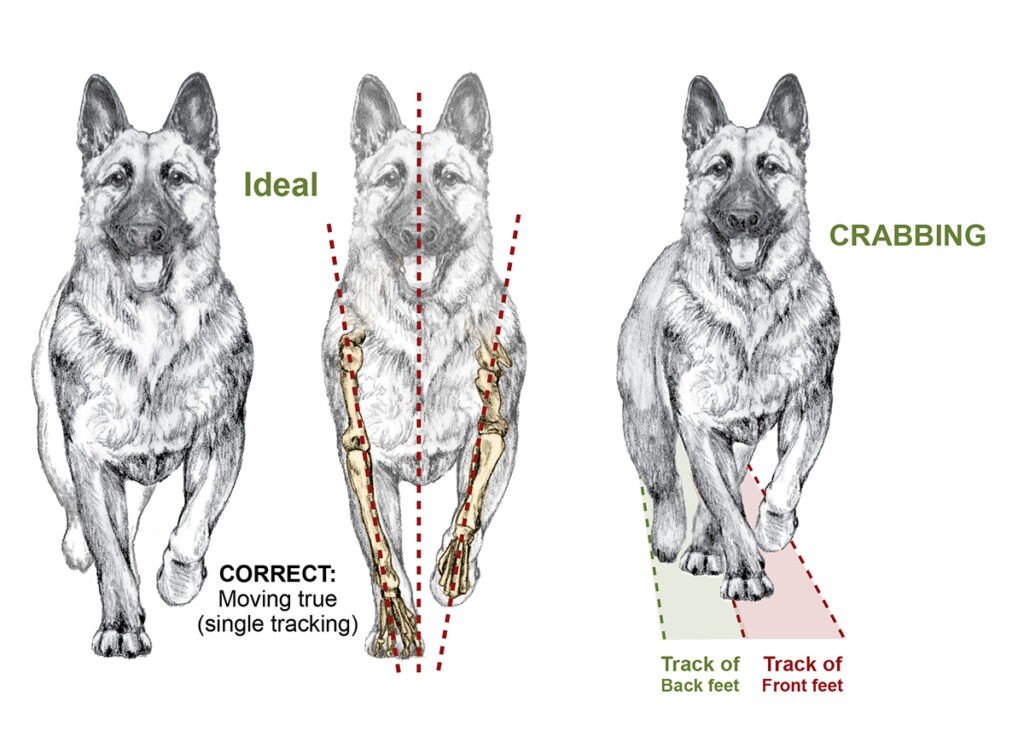

Middle Pieces: The middle pieces are the bones making up the back and loin and are what determine the length of body in a German Shepherd. Dogs that are short coupled (have short middle pieces) do not have enough length of body for proper movement. The dog’s back feet will tend to strike its front feet while gaiting, resulting in decreased reach and crabbing (rear misaligned with front). This is in contrast to the dog that is too long in body and must exert too much energy while in motion.

Topline: The topline runs from the base of the neck, through a high, long withers, into a straight back and towards the slightly sloping croup, without visible interruption. The back is moderately long, firm, strong and well-muscled. The loin is broad, short, strongly developed and well-muscled. The croup should be long and slightly sloping (approx 23° to the horizontal) and the upper line should merge into the base of the tail without interruption.

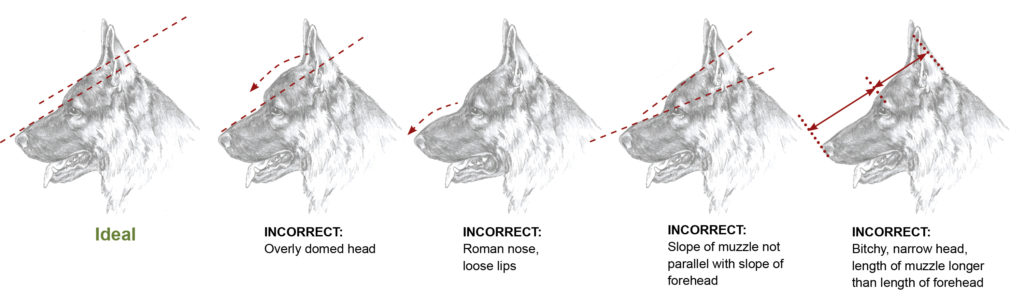

The Head

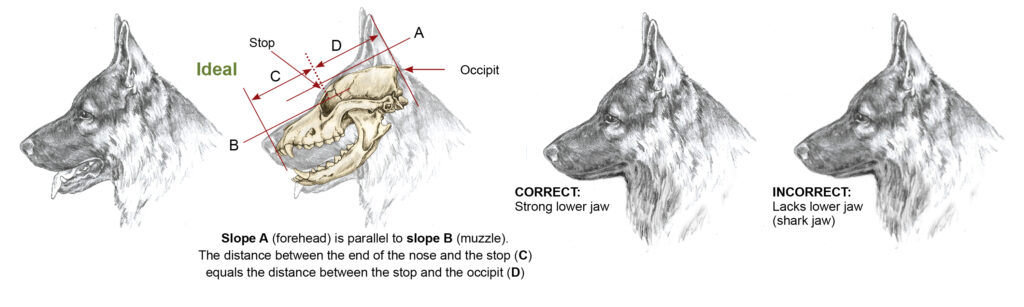

The head of a German Shepherd is noble, cleanly chiseled, strong without coarseness, but above all not fine, and in proportion to the body. The expression keen, intelligent and composed. Seen from the front the forehead is only moderately arched, and the skull slopes into the long, wedge-shaped muzzle without abrupt stop. The muzzle is long and strong, and its topline is parallel to the topline of the skull. Nose is black. Noses that are not predominately black are faulty. Lips are firmly fitted. Jaws are strongly developed.

The slope of a German Shepherd’s forehead should be parallel to the slope of its muzzle. The length of the forehead is measured from the occipit to the stop, while the length of the muzzle is measured from the stop to the tip of the nose.

German Shepherd muzzles should be black and should be at a length equal to that of the forehead. The lips, nose and eye rims should be solid black—even on white dogs. The jaw should be strong and visible when the mouth is closed and the lips should be firm and not sag. On males, especially, muzzles should not appear narrow or snipy.

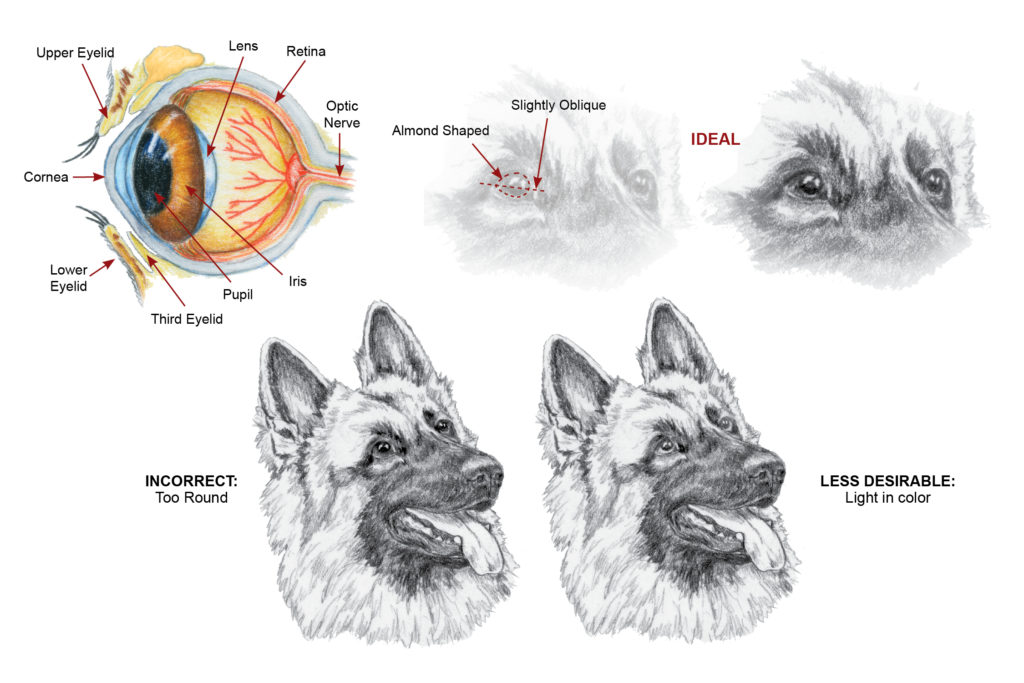

EYES

The eyes of a German Shepherd should be of medium size and almond shaped. Because they are the central component of expression, they should not distract from the overall impression of the head by being too light or protruding. The darker the color the better.

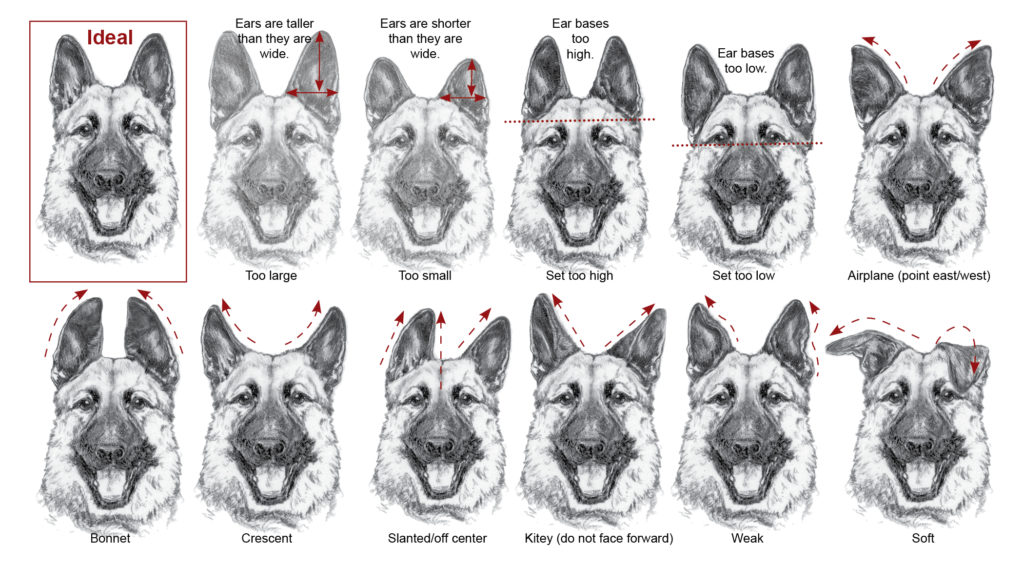

EARS

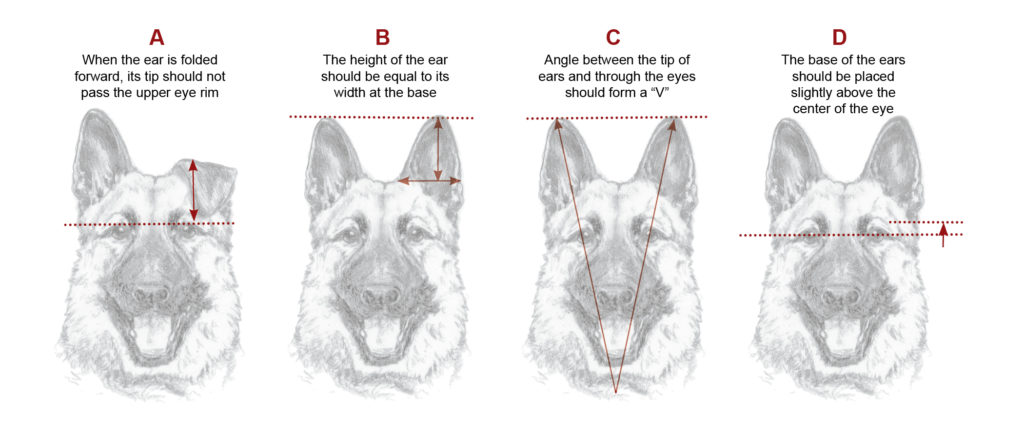

German Shepherd ears are moderately pointed and in proportion to the skull. They open toward the front and are carried erect when at attention. The ideal carriage being one in which the center lines of the ears, viewed from the front, are parallel to each other and perpendicular to the ground.

Ears should be of a size that compliments the overall outline of the head. The height of the ear should be equal to its width at the base.

Any dog with cropped or hanging ears must be disqualified.

To check for size, fold the ear down toward the eye (A). The tip of the ear should not pass the upper eye rim.

In contrast, ears that are too small also detract from the overall look and proportion of a shepherd’s head. The height of the ear should be equal to its width at the base (B).

Lines drawn from the tip of the ears, through the center of the eyes, to the midline of the body should form a “V” (C). The ears should additionally be set high, and well apart, with the base of the ear placed just above the center of the eye (D).

Secondary Sex Characteristics are sex characteristics not related to reproduction. In German Shepherds and other breeds, these characteristics include size, musculature and head and expression. Head proportions—including the angle and length of the forehead and muzzle, and slope of the stop—are identical for both the dog and the bitch.

When examining the head of a German Shepherd, the sex of the dog should be easily apparent. Body size, head and musculature on stud dogs should be quite different from that of bitches. Overly broad, masculine heads on bitches, or studs with more refined, weak or feminine attributes are penalized.

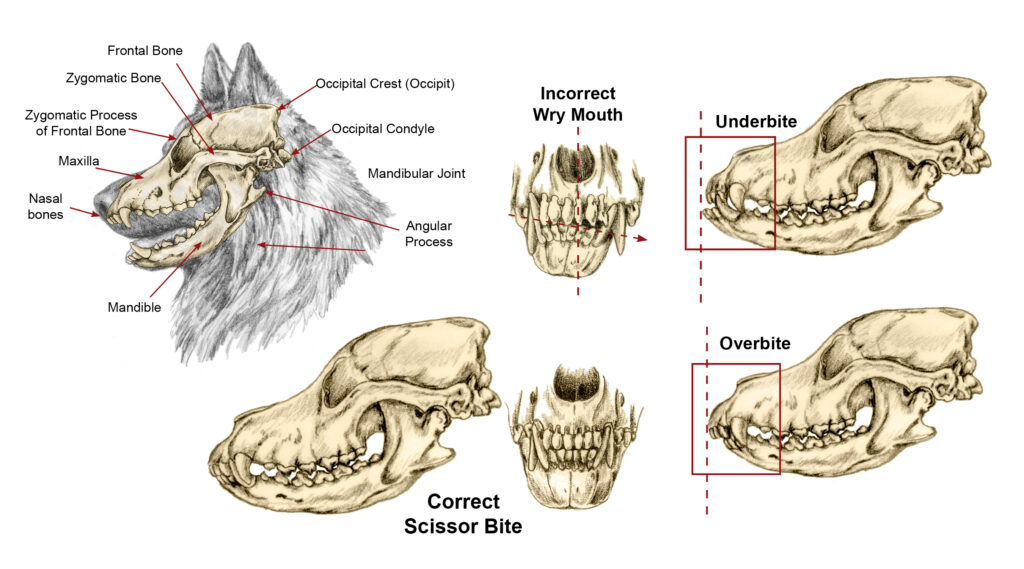

Skull and Bite

Level Bite: The incisors meet edge to edge. This bite is acceptable, but not ideal.

Overshot Bite/Brachygnathism: The upper jaw is longer than the lower and the upper incisors extend beyond the lower incisors.

Undershot Bite/Prognathism: The lower jaw is longer than the upper jaw.

Wry Bite/Wry Mouth: When one side of the jaw grows longer than the other. The canines nor the incisors line up squarely.

Crowded Bite: When the teeth are overcrowded, sometimes overlapping. Dogs with crowded bites usually have narrow jaws/muzzles, or have retained puppy teeth.

Crooked Teeth: Usually caused by crowding in a too-small or too-narrow jaw or the result of damage to the mouth.

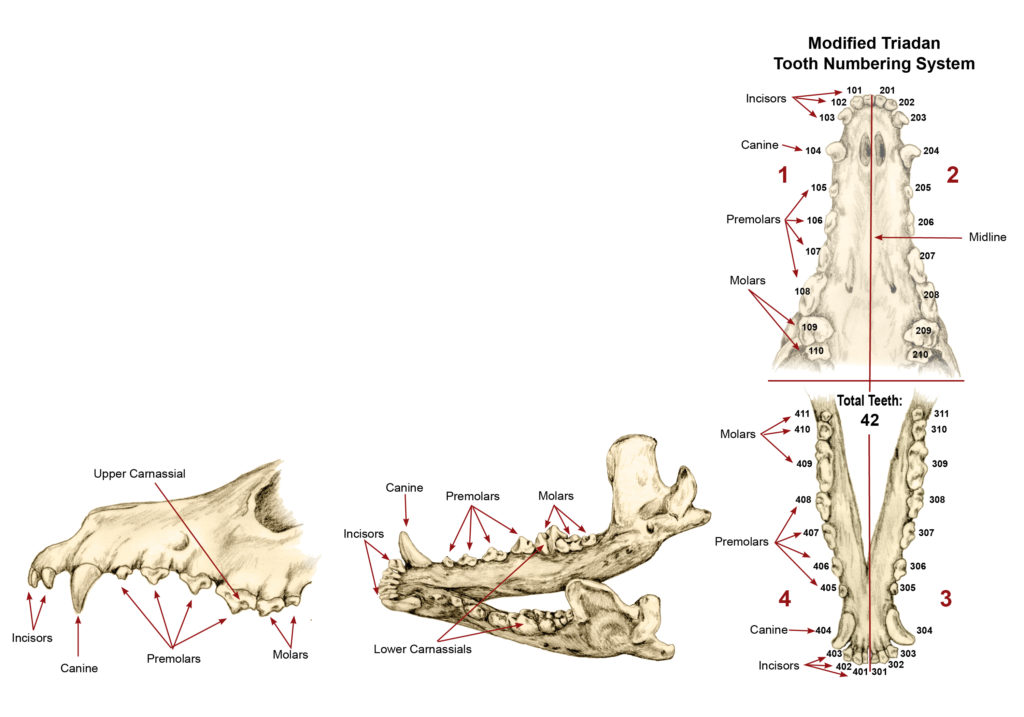

TEETH – TYPE AND FUNCTION

Adult German Shepherds have 42 teeth (20 upper and 22 lower)

Incisors. Used for cutting, scooping, picking up objects and grooming.

Canines. Used to hold prey, to slash and tear while fighting, and serve as cradles for the tongue.

Premolars. Used for holding, carrying and breaking food into small pieces.

Molars. Used for grinding food into small pieces.

Carnassials. Used for cutting food.

Tooth Numbering: Modified Triadan

The modified Triadan system provides a consistent method of numbering

teeth across different animal species. Numbering is as follows:

First digit of the modified Triadan system denotes the quadrant:

• Right upper permanent = 1 • Left lower permanent = 3

• Left upper permanent = 2 • Right lower permanent = 4

Missing teeth are an inherited trait resulting in a weakening of the jaw. The first premolars are the most commonly missed teeth, and though not as serious a fault as missing the second through fourth premolars, or missing multiple teeth, any German Shepherd missing first premolars should not be bred to another dog with this same fault. The pairing could result in progeny with weakened jaws and missing teeth. An overshot jaw or a level bite is undesirable. An undershot jaw is a disqualifying fault. Complete dentition is to be preferred. Any missing teeth other than first premolars is a serious fault.

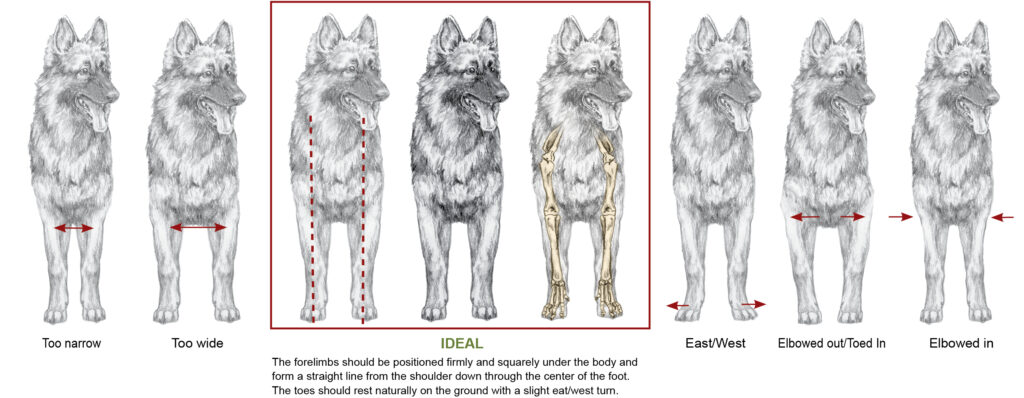

Forelimb Alignment

Chest/Forechest/Ribs

Chest/Forechest: When discussing the chest/forechest of a German Shepherd, we are referring to the triangular part of the body between the prosternum and the highest point of the withers and from the highest point of the withers down to the elbows. Your depth of your German Shepherd’s body at the chest should account for approximately 48% of its height. The bottom line of the chest should align with the elbows and the prosternum should stand out just ahead of the shoulder when viewed in profile.

Commencing at the prosternum, the chest should be well filled and carried well down between the legs. It is deep and capacious, never shallow, with ample room for lungs and heart, carried well forward, with the prosternum showing ahead of the shoulder in profile. Ribs well sprung and long, neither barrel-shaped nor too flat, and carried down to a sternum which reaches to the elbows. Correct ribbing allows the elbows to move back freely when the dog is at a trot. Too round causes interference and throws the elbows out; too flat or short causes pinched elbows. Ribbing is carried well back so that the loin is relatively short. Abdomen firmly held and not paunchy. The bottom line is only moderately tucked up in the loin.

Ribs: Ribs are designed to protect your German Shepherd’s vital organs. Rib bones should be relatively flat and attach to the spine at the top and to the sternum at the bottom. They should be long and carried well back into the body, keeping the loin short and strong. Ribs and rib cages that are too round (barrel shaped) push the elbows out and away from the body while ribs that are too flat and short cause pinching in of the elbows. The rib cage should allow plenty of room for expansion of the lungs. Well sprung ribs that are correctly positioned in the body, function to protect vital organs, yet are flexible enough to allow ample room for proper breathing.

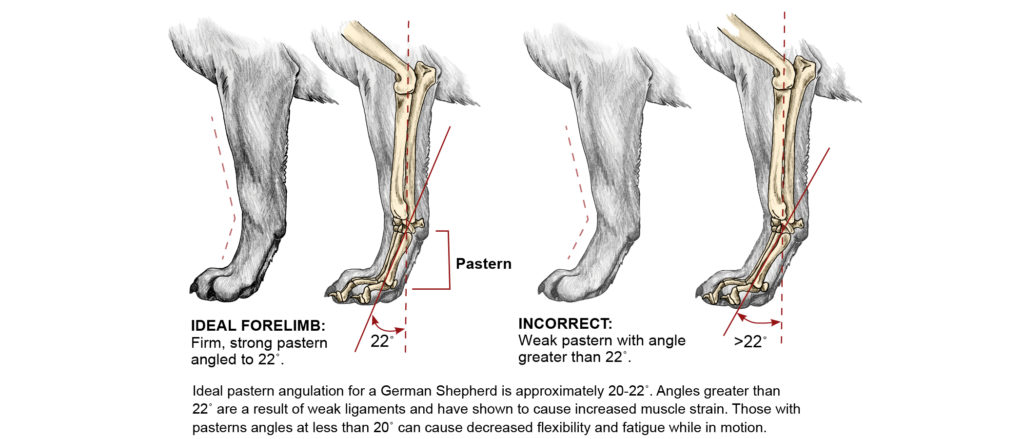

Forelimb

Forelimb: The humerus, ulna, metacarpal and carpal bones provide the infrastructure of the forelimb and play an essential role in supporting your German Shepherd when in motion. The tendons and ligaments however, are what usually dictate correct conformation. The strength, firmness and angle of the pastern provides protection during impact and this cushioning is directly related to the condition and firmness of the ligaments surrounding the joints. Any weaknesses of the forelimbs can make your German Shepherd prone to injury and cause premature arthritic conditions.

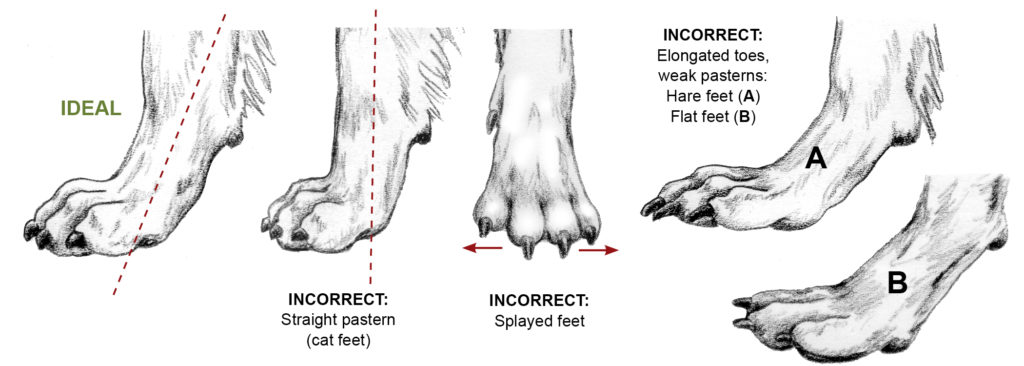

Feet: The feet of German Shepherds should be tight and well sprung. Toes that are elongated or splayed display weak ligamentation with decreased cushion and spring in the foot necessary for efficient, stress-free movement. Splayed, flat or hare feet are serious faults.

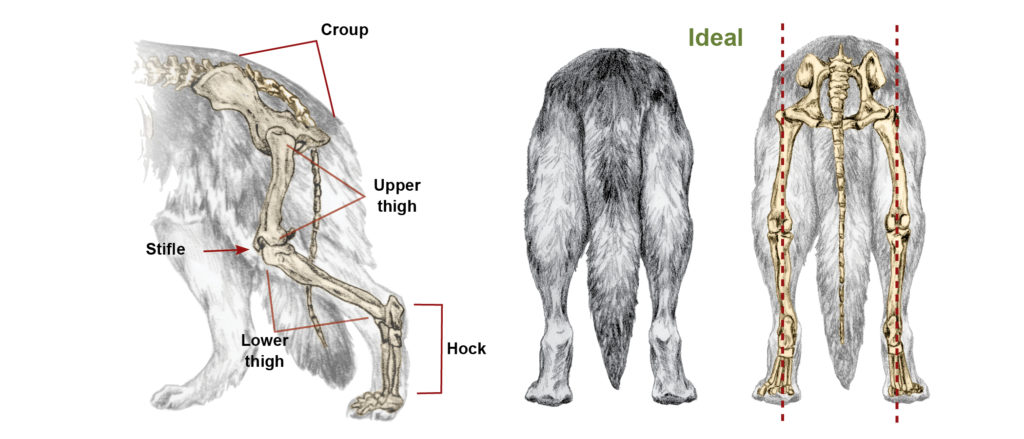

Hindquarters

Hindquarters: When talking about hindquarters on German Shepherds, we are referring to the pelvis, croup, upper and lower thigh, stifle, and hock. These structures combined make up the most critical component of forward motion in your dog. If your German Shepherd has weak hindquarters, its movement will be poor regardless of how well the rest of its body is put together. Forward motion begins from the rear as energy is pushed forward through the body.

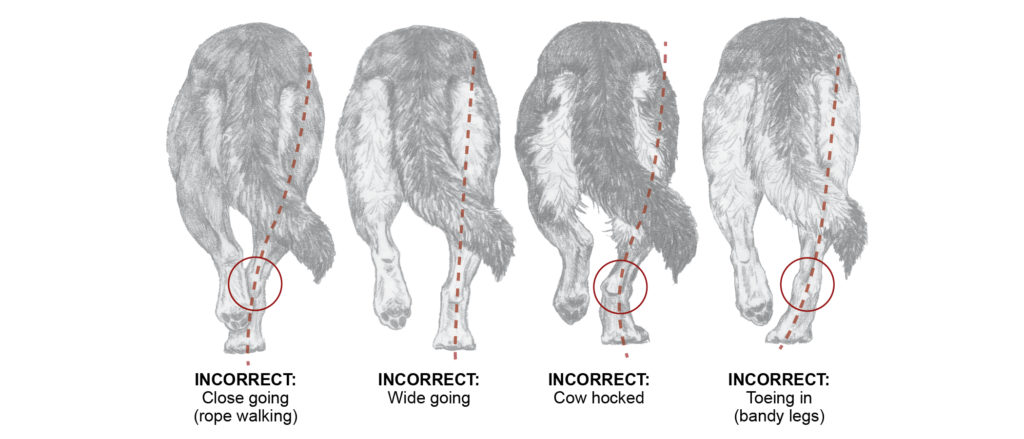

Pelvis: The pelvis is a complex structure that serves as a bridge for the transmission of energy between the rear legs and the spine.

Croup: The croup includes the sacrum and the first few vertebrae of the tail. The slope of the croup is usually determined both by the slope of the pelvis and the position of the tail set. A correctly sloped pelvis is critical for efficient transmission.

Upper and lower thigh: The lower thigh on German Shepherds should be only slightly longer than the upper thigh. The length of the lower thigh plays a large role in determining the degree of angulation in the rear. The longer the lower thigh bones, the greater the angulation.

Stifle: The stifle or knee joint is one of the most complex joints in the body and is where the femur, tibia and fibula join with the patella to form a powerful lever used for forward motion. Any weakness at this critical juncture effects a dog’s strength and stability and makes it prone to injury.

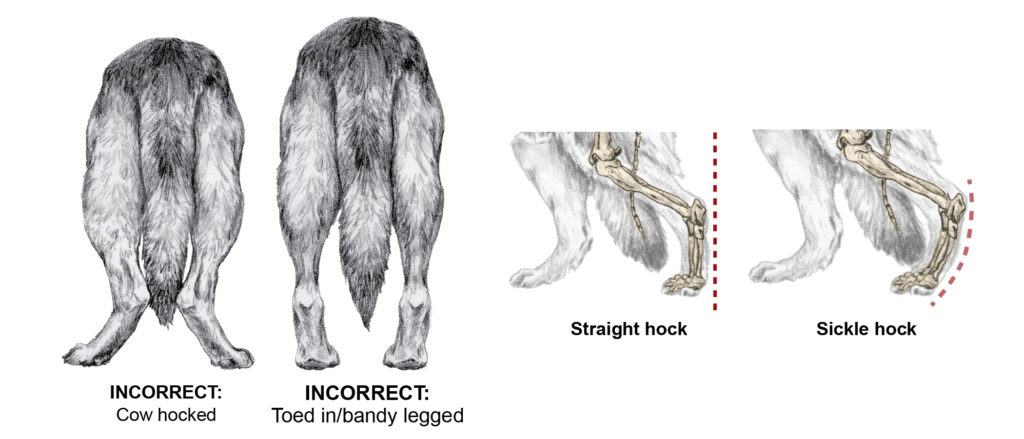

Hock: The hock is where forward transmission begins and, because it is covered with a minimum amount of muscle, it is very susceptible to injury. It is crucial that this joint be straight and not bend either inward (cow hocked) or outward (bandy legged). Sickle hocks are hocks that curve inward toward the body. A slight sickle is good, but a curve that causes the dog to walk with its hocks low to the ground like a kangaroo is considered faulty.

Tail Set/Carriage

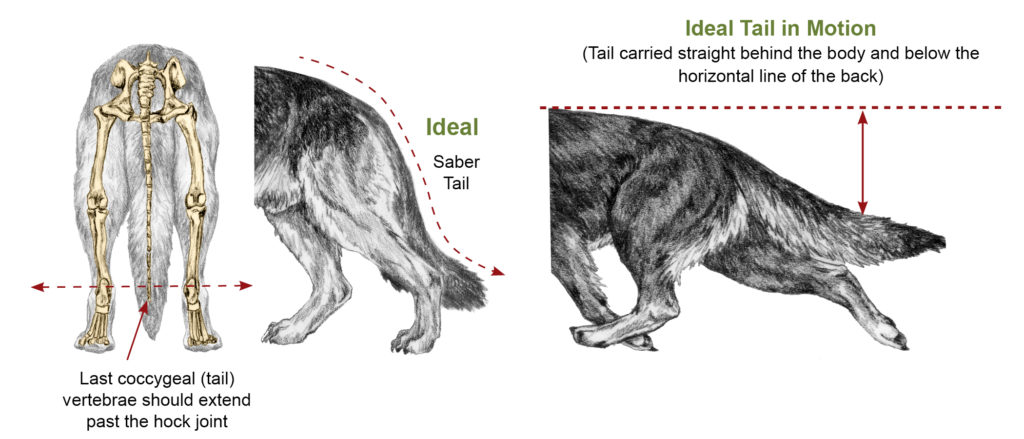

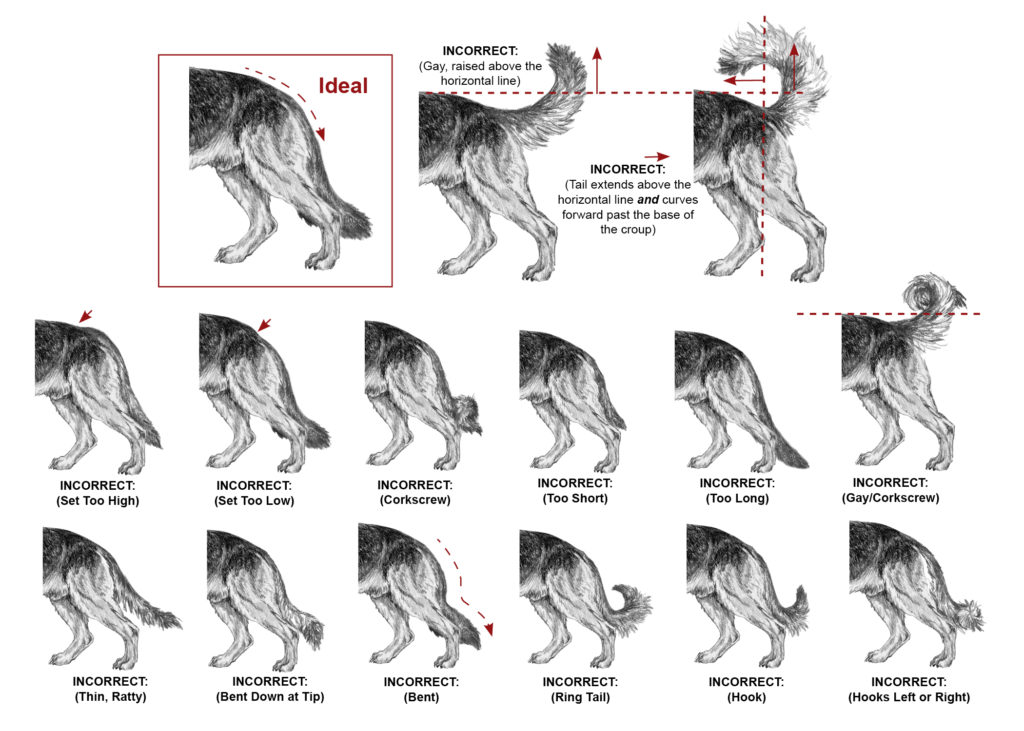

Tails: When standing in a relaxed position, the tail of a German Shepherd should transition smoothly from the croup, be densely coated, and hang gracefully from the body. When viewed in profile, the tail flows gently downward with a slight curved (saber) appearance. The last coccygeal (tail) vertebrae should extend past the hock joint.

The tail set (the point of the croup where the tail begins) should be smooth and not bulge or dip. Tails that are set too high tend to form a bulge or tuck of hair at the base of the croup, while tails that are set too low will usually display a dip before transitioning in the tail. Very low tail sets might can also increase vulnerability to perianal fistula in some dogs.

The body of a German Shepherd’s tail should not exhibit any curls, bends, twists, or other structural defects and should be densely coated on both smooth and plush coated varieties.

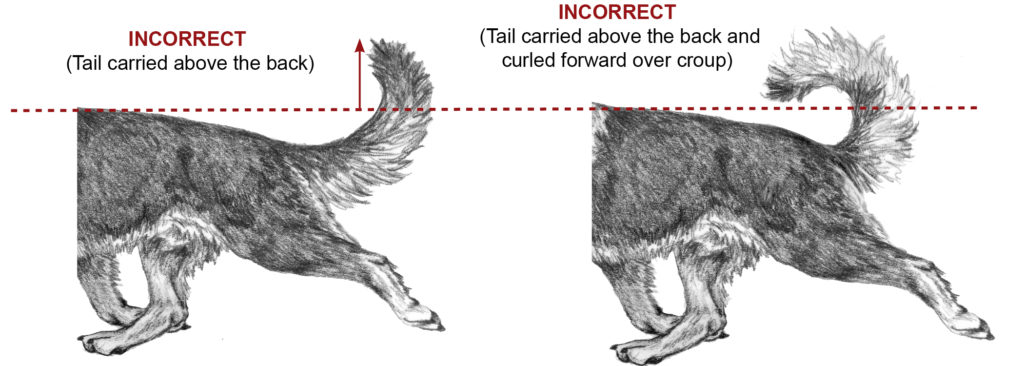

While in motion, the tail can be raised—but should not extend above the horizontal line of the back. Nor should it be rolled up over the back past the base of the croup. While tails that raise above the horizontal line of the back are acceptable during periods of excitement or arousal, it should never be displayed in the conformation ring, and especially while in motion.

Because of the difficulty of breeding out tail faults, any tail that is carried above the horizontal line of the back is considered a serious fault. Tails that extend above the back and curl forward past the base of the croup are considered a very serious fault.

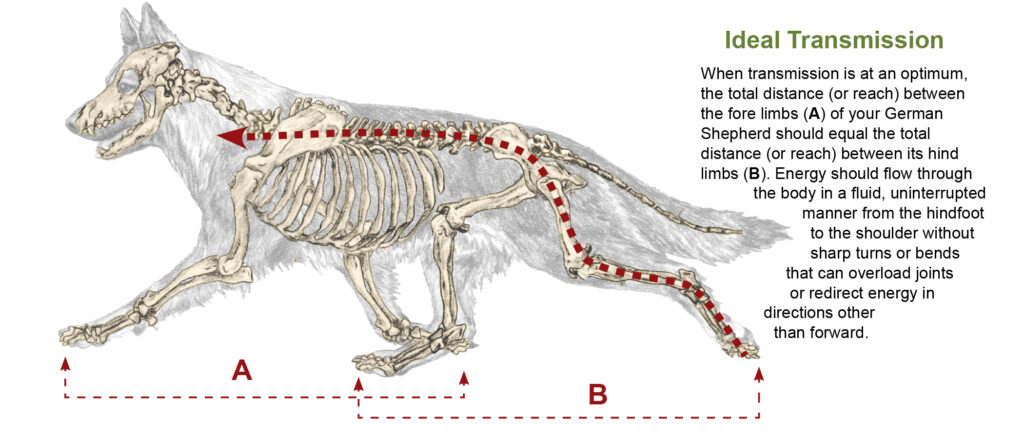

The German Shepherd in Motion

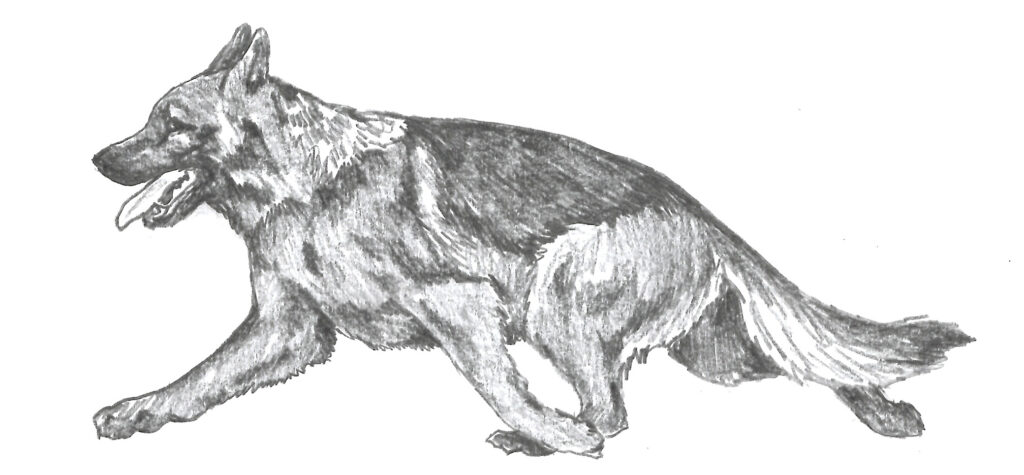

SUSPENDED TROT

Suspended Trot – There is a period of suspension in which all four feet are off the ground.

perfectly balanced dog, this effortless, rhythmic stride gives the illusion of slow motion and is spectacular when observed. A German Shepherd capable of performing a suspended trot is one with tremendous strength of back and one whose front and rear assemblies work harmoniously together.

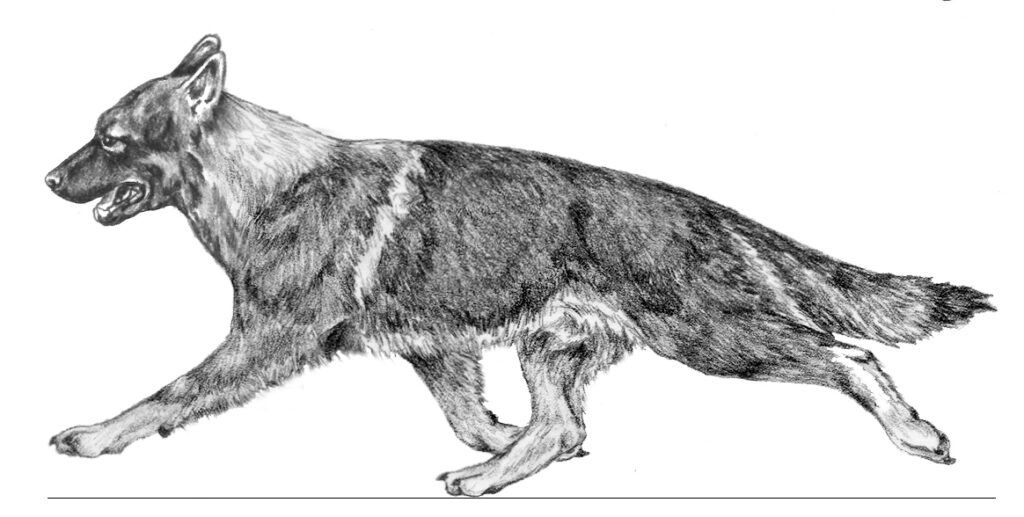

FLYING TROT

Flying Trot – There is no period of suspension. The hindfoot touches down before the forefoot even begins to be lifted.

There is a point in which the reach of a German Shepherd can be too extreme. Though flashy, some of these loosely ligamented dogs, with exaggerated reach, perform poorly at normal activities such as jumping, and some can have difficultly even standing or walking without appearing off balance. Notice also the tremendous pressure placed on the hocks due to their relative position to the ground.

PACING

There is a third gait called pacing. Pacing is when the legs on each side of the body move concurrently in the same direction. This action causes your dog to bounce and roll from side to side while in motion. Pacing is the easiest of the three gaits to perform. If your dog is pacing, it usually means you are not running fast enough for your German Shepherd to transition into a full trot or your dog is tired, overweight or conformationally deficient (short coupled, under angulated, etc.). You should avoid pacing while in the ring. Your dog will appear clumsy and the judge will be unable to properly evaluate its gait or transmission.

LOAFING/LUMBERiNG

With increased size, you inevitably loose flexibility and agility. Very large German Shepherds and/or dogs that are conformationally deficient, might not be capable of performing either a flying or suspended trot. These dogs will, instead, loaf, lumber and/or bounce while in motion. Their bodies roll from side to side and their reach is greatly diminished. Dogs of very large stature must be in top condition and be tightly ligamented to successfully compete against smaller, more agile competitors. Shoulders that roll from side to side, and backs and abdomens that bounce while in motion, are typical of large, loosely ligamented dogs.

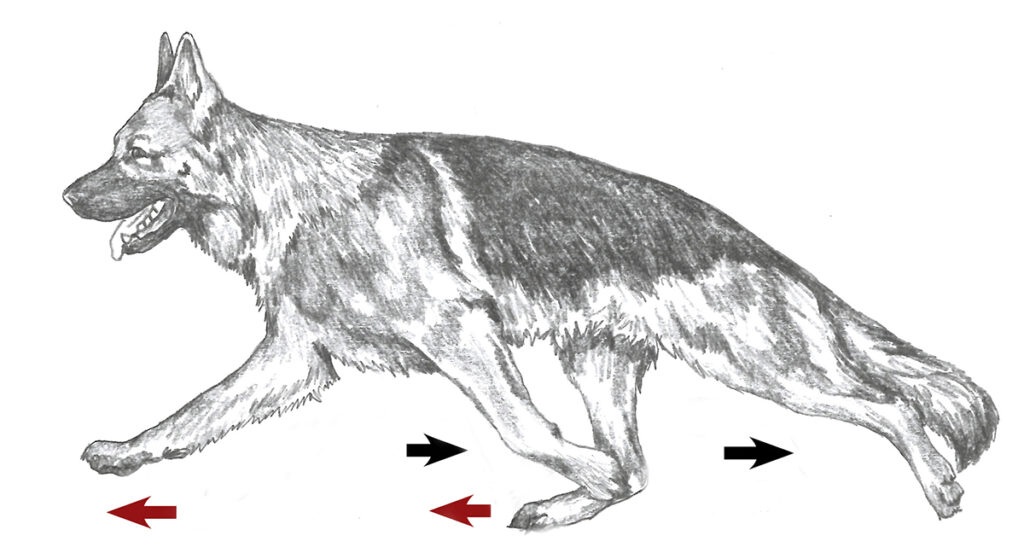

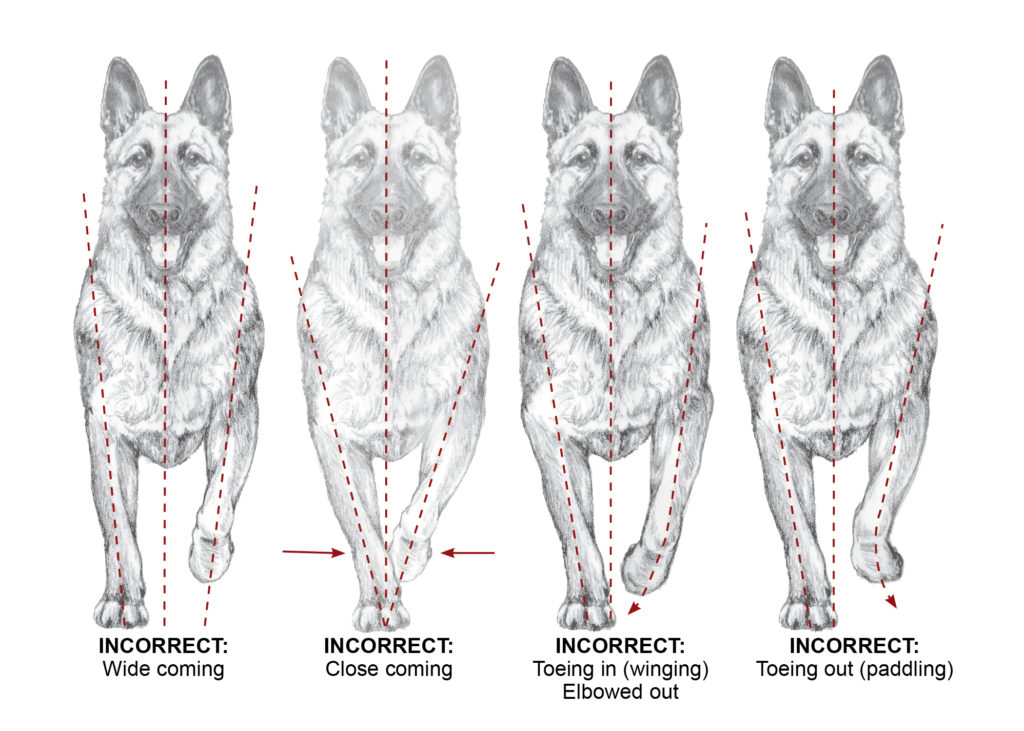

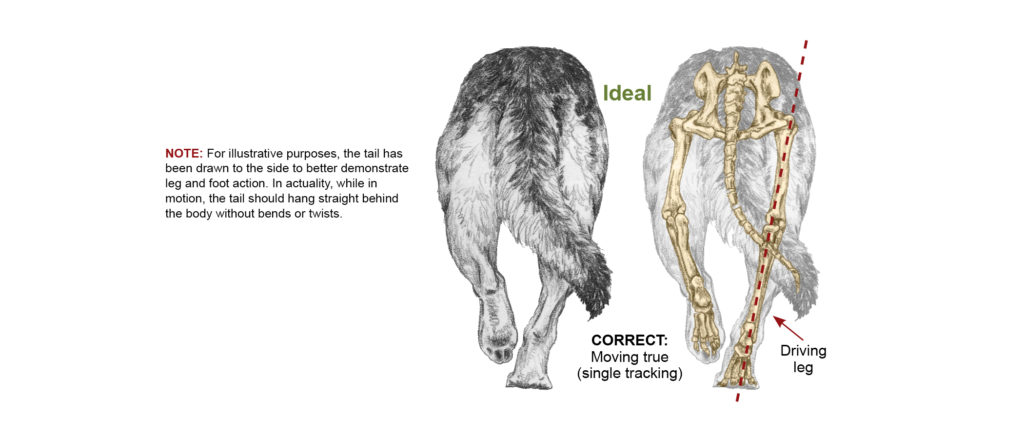

ACTION COMING

When viewed from the front, judges look for balance and ease of motion. As forward action begins, the forelegs move toward the midline of the body. This shift—or single tracking—increases balance and conserves energy. The forelegs should hold firm in a straight line from the shoulder joint to the toes. A German Shepherd that is wide coming wastes a lot of energy by carrying its feet too far away from its midline and this usually results in a choppy, side-to-side motion. Dogs that are close coming (front feet cross over) are not balanced and also loose valuable energy. Crabbing, or moving crabwise, is a term used to describe a condition where the front and rear of the dog move in two parallel tracks side by side instead of a single tract down the midline. This occurs when the front or rear overpowers the other. Energy is lost with any shift of energy in a direction other than the direction your dog is moving.

ACTION GOING AWAY

While going away, judges look for powerful, straight lines in the driving leg. Any joints that are not straight are highly susceptible to injury due to the tremendous force applied to these areas when in motion.

As the rear leg is brought forward, a well conditioned, well muscled German Shepherd will show some shifting of the leg away from the midline at the knee. This is normal and is indicative of good muscling. However, you should not see any twisting or extreme pushing out of the knee. Poorly conditioned dogs, or individuals lacking muscle mass will move flat, holding both legs too close to the body. These dogs frequently show weakness of back, as well, and a shifting or rolling of the body will be observed both coming and going. A German Shepherd with good movement going will show great firmness of back, dense muscling and an even pressure applied to joints. Any deviations in structure can greatly increase energy loss and fatigue, and in the long term, could result in permanent damage to the affected joints. The illustrations below show how any curve at the hock creates added stress on the joint. Only a dog that is wide going retains a straight line on its driving leg, but looses energy because its legs are too far away from the midline of the body.

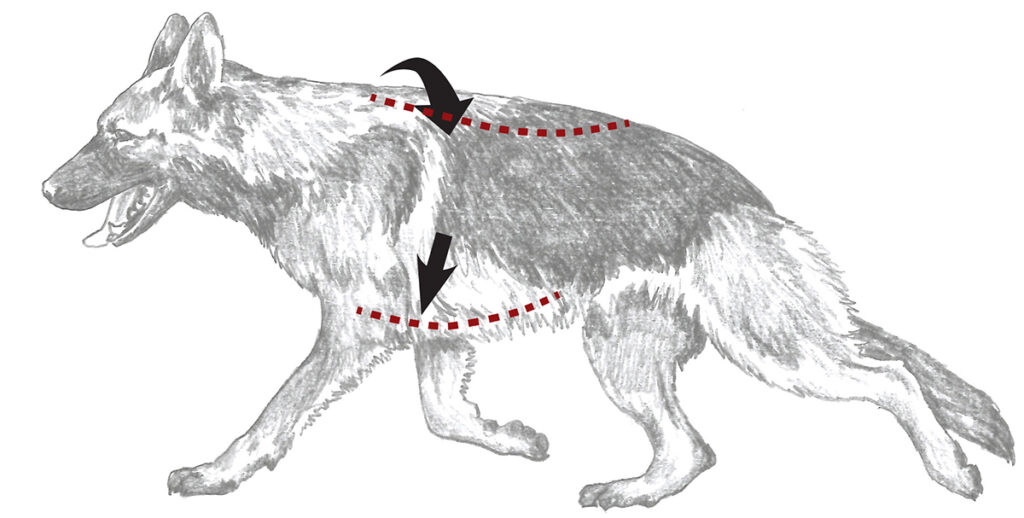

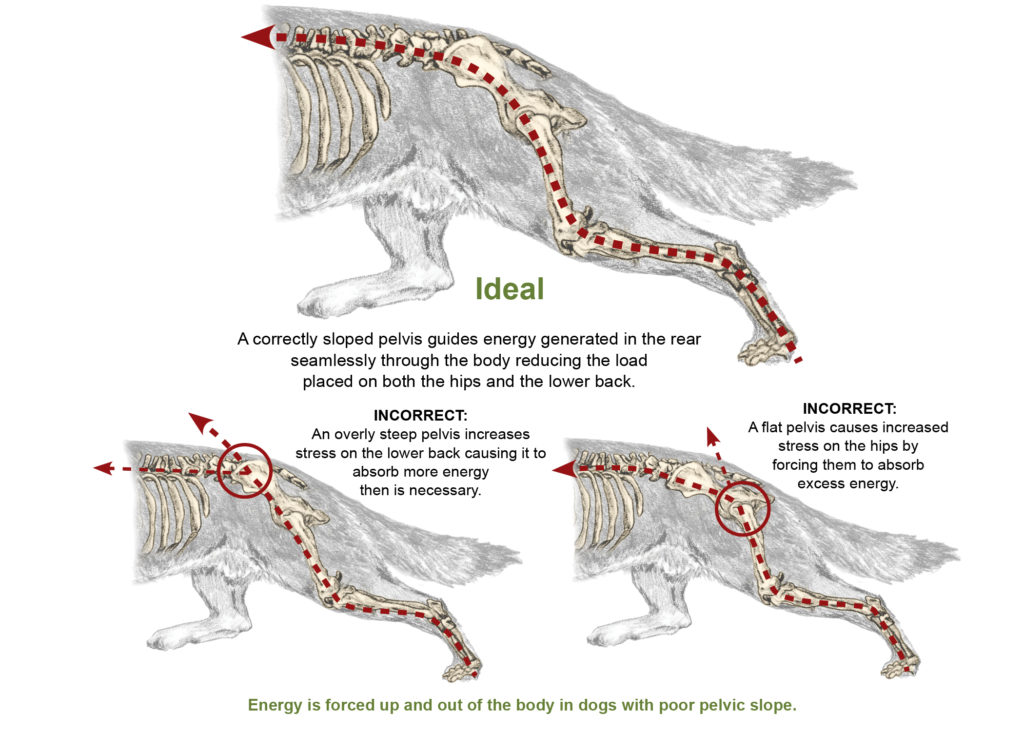

Transmission - What It Is and How It Affects Motion

The loin/back is another critical component involved with transmission. Once energy passes through the pelvis, it moves into the spine toward the forehand. A strong, firm loin/back is essential. Any weaknesses will cause the dog’s torso to bounce or sway as it moves. This up and down, or side-to-side motion, causes energy to be misdirected and move in directions other than straight forward. While in motion, the back should remain straight and firm.

The forequarters of your German Shepherd generates only a fraction of the amount of energy that its hindquarters produce, but it is equally important because it serves as support for the front of the dog and controls braking and steering. The shoulders must be able to absorb the energy generated from the rear without interfering with it. For this to happen, your German Shepherd’s front reach must equal its rear reach. Its front legs must be able to cover the same amount of ground as its corresponding rear legs. The shoulders of a German Shepherd must be correctly angulated, the upper arm should not be too short, and the withers should be high and well muscled.

As mentioned previously, conformation faults cause energy to be misdirected from the body. Aside from the obvious disruption in movement, these faults can cause additional stress to be placed on your dog’s joints, making it more susceptible to injury and premature arthritic conditions.

Any faults in gait or transmission are very serious in German Shepherds and should be penalized.

Conformation faults have the greatest impact on transmission. If the basic bone structure of your German Shepherd is lacking, no matter of muscling or conditioning is going to improve your dog’s transmission or reach. Below are a couple of examples of how a short upper arm or short lower thigh might restrict your dog’s reach. If reach is restricted, transmission will also decrease.

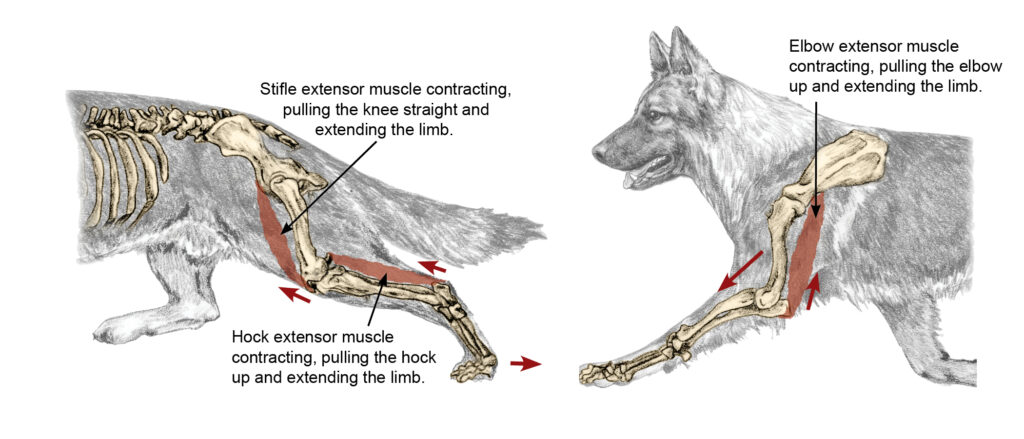

Flexor and extensor muscles surround your German Shepherd’s jionts. Flexors pull the joint closed and bring the limb close to the body. Extensors open the joint and straighten the limb out and away from the body. If your dog has a short upper arm, it will have short extensors. Short extensor muscles cannot contract enough to adequately extend the limb. The same theory applies to the hindquarters. The longer the lower thigh bone, the longer its associated muscles. Longer muscles can contract more and extend the leg further than short muscles.

Now that we understand the fundamentals of transmission and it’s importance in the overall function of the dog, the question becomes, at what point does too much of a good thing become a not so good thing? The German Shepherd Dog was designed to be the ultimate trotting dog. Breeders have become obsessed with creating a dog capable of extreme ground coverage and speed. Show line German Shepherd Dogs are now covering an insane amount of ground in a very short period of time.

BUT WHY? Why do German Shepherds need to cover a tremendous amount of ground in a short period of time? What function does this skill serve outside of the show ring? What are the resulting physical limitations of these dogs when they are not gaiting? Are they stable on their feet while standing? Can they walk with a smooth, natural stride without appearing off balance? Breeders worldwide no longer ask these questions. The quest for even greater rear power and extension remains a priority over overall health and stability.

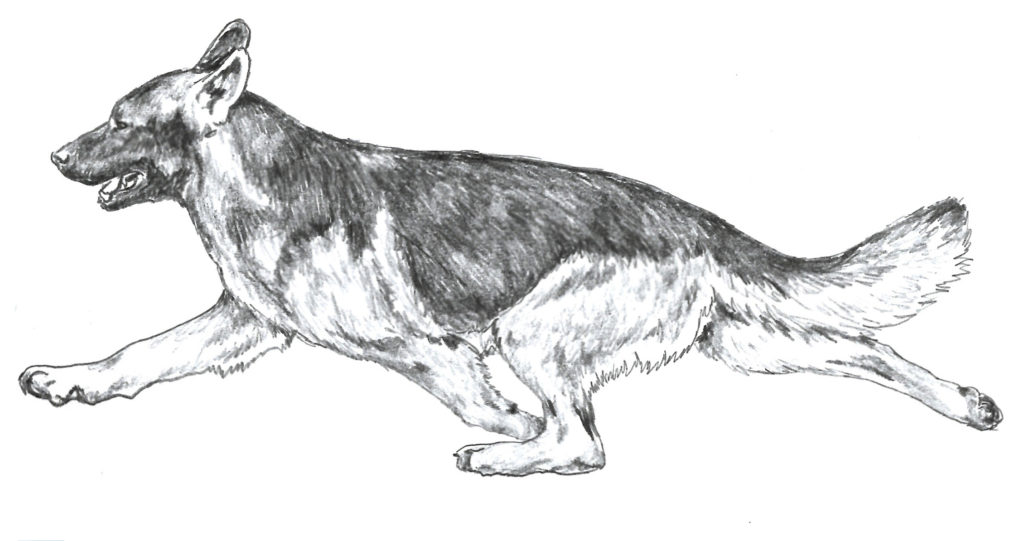

The illustrations below show the evolution of body type and transmission of the German Shepherd Dog. Yes, breeders have become pioneers at “flattening” the curve to allow for a smoother transmission of energy from the hock through to the forequarters. Rounding of the back/loin, a steeper slant to the pelvis and longer lower thigh bones, make the power coming from these dog’s hindquarters—tremendous.

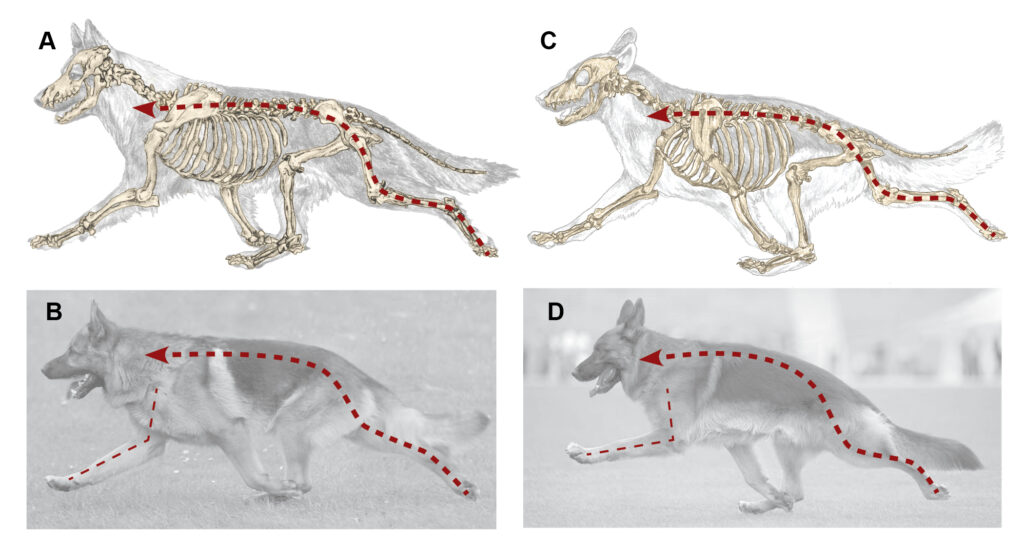

Once this tremendous power passes from the pelvis into the loin/back, it moves into the front assembly. The dog’s front must be equally powerful to absorb the tremendous power moving into it. Illustrations A and C show well balanced dogs in motion. It is possible to maintain balance in a dog with an over extended reach (C), but it is not typical, and these dogs can appear less stable while standing or walking. Photo B is an example of a moderately angulated, balanced dog. Yes, there is a slight misdirection of energy up and out of the body at the hip/pelvis juncture, but the energy that moves through to the front does not overpower the dog’s forelimbs. This dog will be able to stand or walk steadily—with ease and balance. Photo D shows a dog with tremendous rear strength that is completely over powering its front. To compensate, the dog must throw up it’s front legs in an effort to increase front reach. Its short upper arm is also restricting reach. Notice the front reach between dogs B and D is approximately equal, but dog D is working twice as hard attempting to maintain front/rear balance. Dog D can sustain this type of gait for only a short period of time before exhausting. It’s endurance is therefore much lower than that of dog B.

Below are examples of dogs with their weight evenly distributed over the length of their bodies and also dogs with extreme angulation that shift a disproportionate amount of weight onto their stifle and hock joints. These over angulated dogs are much more susceptible to injury at these critical junctions.

Learn more about the transition of the breed under our “Then and Now” tab in the GSD Menu bar.